Find Luke‘s other articles On Brussels here.

There is now a distinct, tangible light at the end of the impossibly long Covid-19 tunnel. Brussels is now approaching that light. But this past month has thrown up fresh sets of challenges involving two of the EU’s most complex and fraught bilateral relationships — as well as uncomfortable realities from within.

On 23 May, the EU received an almighty shock to the system. In scenes that could have come straight from a Cold War film, Ryanair Flight 4978, en route from Athens to Vilnius, was forced to land in Minsk. The plane was crossing through Belarusian airspace. As it neared the Belarus-Lithuania border, air traffic controllers in Minsk informed the crew that a credible bomb threat had been made against the plane by Palestinian militant group Hamas. Despite the nearest airport being its destination of Vilnius, Flight 4978 was escorted to Minsk by Belarusian fighter jets.

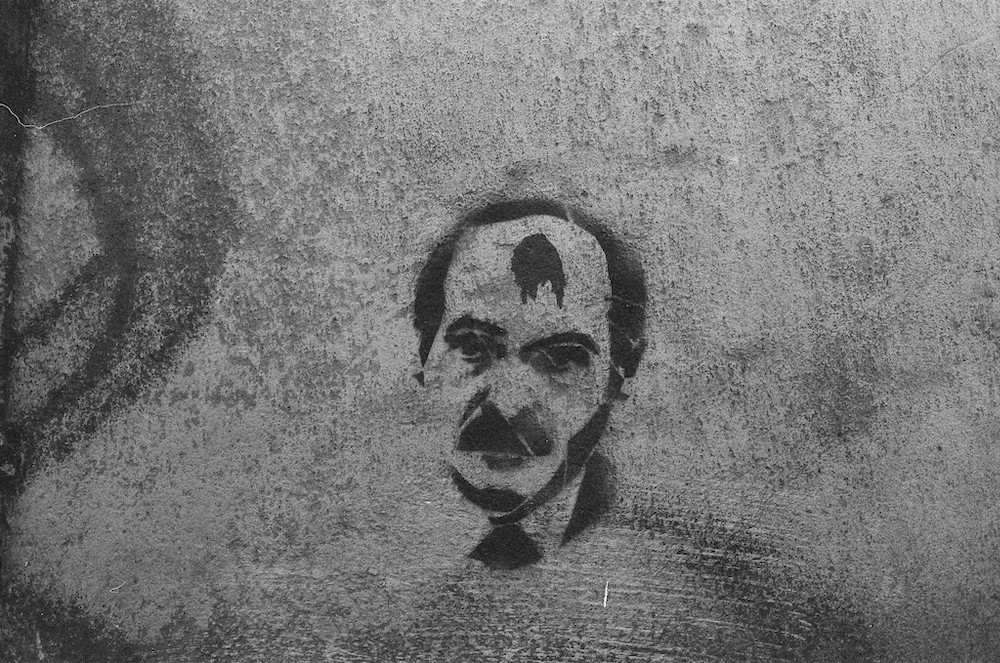

Among the 132 people on board was Belarusian opposition activist and journalist Roman Protasevich and his girlfriend, who had both fled to Lithuania during the 2020 protests. After the plane landed in Minsk, both were promptly arrested. The pair are now allegedly facing inhumane conditions and torture. If convicted of crimes against the state, Protasevich could face death. Belarus is the last country in Europe that retains capital punishment.

The condemnation was deafening. Countries that agree on very little, like Hungary and Luxembourg, lined up to condemn the actions of the Lukashenko regime. In fact, the only major power to stand by Belarus was Moscow.

The Minsk-Moscow relationship is not so much one of friendship as it is one of dependency. Minsk depends on Moscow to keep its economy afloat and its citizens in-check. Moscow depends on Minsk to stay within its sphere of influence. Having lost Ukraine, Belarus is the last EU-Russia buffer zone. Were Belarus to begin democratisation, it is likely that the entirety of Russia’s western borders would soon be in NATO or NATO-aligned. Belarus is useful to Moscow.

On 26 May, the EU closed its airspace to Belarusian aircraft. A package of sanctions against the regime was also announced. Soon afterwards, Ukraine, Belarus’s neighbour to the south, also closed its airspace. Belarusian aircraft can now only head east; the country is now almost entirely enclaved. In response, Russia turned back several EU flights. On 1 June, several Air France, Lufthansa and Austrian Airlines flights bound for Moscow and St Petersburg were forced to divert to either Estonia or Finland.

However, this does appear to have been no more than a little “tit-for-tat” by Moscow. Russia only barred a handful of flights and soon stopped as suddenly as it had started. In what is perhaps the best explanation of the Moscow-Minsk relationship, the Russian government issued a statement saying that the “problems” that led to the flights being rejected were “purely technical” and should not “become an additional irritant in Russia’s relations with the European Union”. In essence, Moscow had made its point, the rest of the mess is Minsk’s to own.

The EU was still reeling from the actions of Minsk when its ever-twisting relationship with Israel reared its head once again. Mere weeks after the 2021 Israel-Gaza War ended in a ceasefire, the government in Jerusalem collapsed.

Israel has dealt with a lot of political instability in recent years. The country has held four elections in two years. Each has produced an inconclusive result, with parties either unable to form governments or highly unstable coalitions quickly collapsing. The day after Russia turned away several flights, a rainbow of parties signed a coalition agreement. Representing everything from the centre-left to the far-right and from Jewish Nationalism to Arab Israelis, the eight parties were drawn together with one goal in mind: oust Netanyahu. Benjamin Netanyahu, Israel’s longest-serving leader, has become increasingly divisive in recent years. He has increasingly pandered to the right of his Likud party – as well as to ultra-Zionist voters. His detractors see him as a threat to the very existence of Israel. His supporters call him King Bibi. On 13 June, following a parliamentary vote, the King lost his crown. With a one-seat majority, the rainbow coalition took power, with hard-right Naftali Bennet at the helm.

Bennet may sit to the right of Netanyahu, but the hope is that the new rainbow coalition will be able to reign in his worst impulses. Only time will tell. The formation of this new government may only sound like a domestic Israeli matter, but it will have repercussions in the EU too.

Israel is one of the bloc’s most important partners — but also one of its most controversial. Aside from the ongoing occupation of Palestinian lands, Netanyahu has spent the last few years cosying up to the bloc’s two problematic members: Hungary and Poland. He has also cemented strong working relationships with the Czech Republic and Greece. Budapest, in particular, has become a strong friend of Netanyahu-led Jerusalem, as both Viktor Orban and Benjamin Netanyahu seek/sought to create “illiberal democracies”.

Politically-speaking, Naftali Bennet is far more closely aligned to the likes of Viktor Orban and Andrzej Duda than he is to Angela Merkel or Pedro Sanchez. However, if he is to remain in power, Bennet will almost certainly have to embark on a more centrist path in his dealings with Brussels. If he does not, Brussels may be forced to reassess its relationship with Jerusalem, as it nearly had to following Israel’s threat to annex most of the West Bank in the summer of 2020.

There is, however, one continual stark reality for Brussels. Neither Belarus nor Israel are actually EU members. Deep relations with both Minsk and Jerusalem are a nicety, not a necessity. This returns Brussels to an uncomfortable question for which it still has no answer: how do you deal with a member states that goes rogue?

On 20 May, Poland unveiled its new history syllabus. Normally, this would be of no consequence. However, the new syllabus will teach young Poles that the EU is an “unlawful entity”. The new curriculum will also remove any trace of “unflattering” Polish history, such as Polish collaboration with Nazi Germany during WW2. So far, Warsaw has been unable to give a concrete reason as to why it has chosen to do this. Whilst Warsaw attacks the EU itself, Budapest attacks a minority. On 16 June, the Hungarian government passed a law banning “LGBT propaganda”. Nearly identical to Russia’s anti-gay law passed in 2013, the legislation bans any mention of words like “gay”, “transgender” and “bisexual” to young people under any circumstances.

The EU is exploring sanctions against Hungary, but, come what may, Warsaw and Budapest will always have one another’s backs. Far from being temporary lapses, the Polish and Hungarian backslides look as though they are here to stay — and have become part of the EU’s post-pandemic new normal.