This article is the part of a series by the IFLRY Climate Change Programme, looking at how different countries are implementing the Paris Agreement. An introduction to the series can be found here.

The United States of America (USA), is a federal republic and representative democracy in North America. It is the world’s fourth-largest country by land area and the third most populous country. The capital is Washington,D.C., and the largest city by population is New York City. The United States is a highly developed country, with the world’s largest economy by nominal GDP. The U.S. economy is largely post-industrial, characterized by the dominance of services and knowledge-based activities, although the manufacturing sector remains the second-largest in the world. Although its population is only 4.3% of the world total, the U.S. holds 33% of the total wealth in the world, the largest share of global wealth concentrated in a single country. The United States is the foremost military power in the world, making up a third of global military spending, and is a leading political, cultural, and scientific force internationally.

It has been a little more than one year since Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the ParisClimate Agreement. Throughout his presidential campaign, Trump assailed the Paris Agreement for its supposed attack on American workers, namely those who work in industries that produce oil, coal, and gas – claiming that the Agreement favored developing countries like India, because they don’t have such industries. Apart from using economics to justify the withdraw, Trump has also tapped into a long-standing aversion that many Americans have with becoming involved in international treaties. At stake is the world’s strongest military and economic power distancing themselves from the rest of the world on the issue of climate change, as part of a broader disengagement from the international stage.

The Clean Air Act, enacted in 1963 (and modified in subsequent years), is the most comprehensiveAmerican law governing air pollution. In 2016, the United States, under former president Obama, committed to reduce its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions levels by 26-28 % by 2025, compared to 2005 levels, with an additional commitment “to make best efforts to reduce its emissions by 28%” as part of its nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

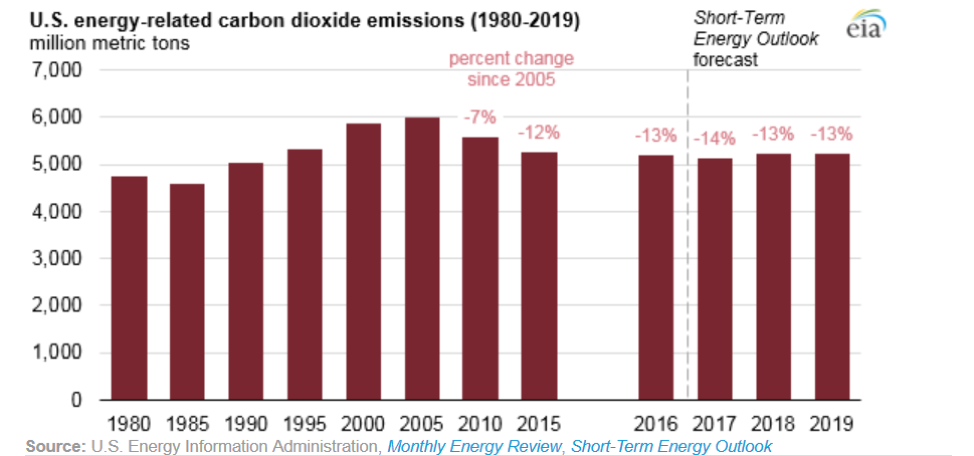

Image 1:

According to short-term projections by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), the United States is likely to experience relatively flat levels of carbon emissions between 2017 and 2019(see image 1). In 2015, the United States emitted the second largest number of metric tons of carbon dioxide: 4997.50.[1] For comparative purposes, the next three highest-emitting countries (India, Russia, and Japan) emitted less metric tons than the United States, combined.[2]

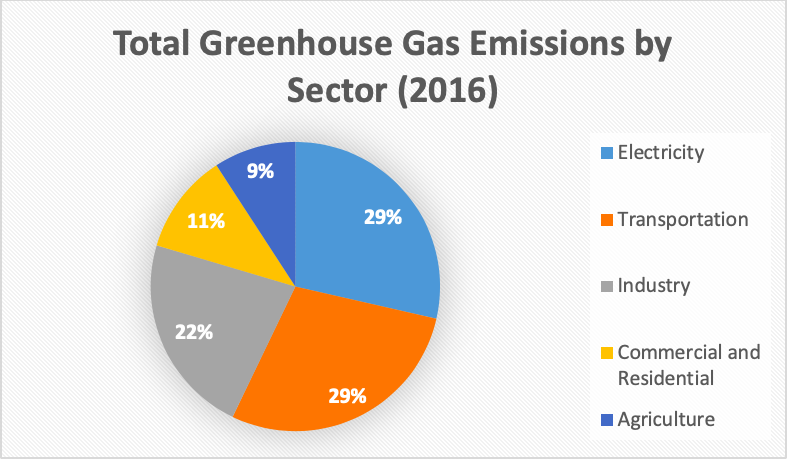

Image 2:

The two largest CO2 emitting sectors in the United States are electricity and transportation, both accounting for29% of overall emissions each. The second biggest source of CO2 emissions is industry, which produces goods and raw materials; the other two are commercial/residential buildings and agriculture, which account for 11% and 9%of CO2 emissions respectively.[3]

There are many creative solutions that would help the United States to bring CO2 emissions levels down in each of these sectors, bringing us into compliance with the NDC set out in Paris.However, implementing these solutions is a fierce uphill battle. There are three major obstacles that constrain our ability to successfully meet the NDC submitted as part of the accords.

First, the United States is the world’s largest consumer market. Americans make up the lion’s share of worldwide consumption of goods, be it automobile use, electricity, or shampoo products – each of which have contribute to global warming. The average American emits 16.2metric tons of CO2 per year, which is significantly higher than the world average of 4.97.[4]Rising seas, droughts, and other environmental calamities are not strongly felt here in the U.S. As a result, people do not empathize. Trends like these are not reversed overnight.

The second challenge comes from large oil and gas companies, which wield a disproportionate amount of influence on American politics. This sector shells out millions of dollars in order to back electoral candidates that are most likely to deter any kind of legislation aimed at enhancing environmental protections, or holding oil and gas companies accountable for their role in CO2 emissions. The five largest campaign contributors in 2017-2018 from the oil and gas industry were Koch Industries,Marathon Petroleum, Chevron Corp, Stewart and Stevenson, and Crownquest Operating. Together, they donated $26.1 million to Republican candidates and conservative groups.[5] Companies of the like have influenced elected officials to pull us out of environmental accords in the past, such as the Kyoto Protocol that President George W. Bush infamously chose to withdraw the United States from. These companies will fight tooth and nail to make sure the United States does not take any bold steps to improve air quality, and reduce emissions.

And finally, the federal government under President Trump has taken a stance on climate change that can be considered stand-offish at best. By removing the United States from the ParisClimate Accords, America is now the only country in the world that has not signed off on the agreement. Trump has managed to stroke the worst fears of a large segment of the American populace that views globalization is dangerous and disruptive, allowing him to lambast most major international treaties and conventions that the United States has historically taken the lead on.

However, not all is doom and gloom for the state of American environmentalism. One year ago, a compact of 20 states and 50 cities in the United States came together to form what is known as America’sPromise. The purpose of this group – led by the governor ofCalifornia, Jerry Brown, and the former Mayor of New York City MichaelBloomberg – is to continue America’s commitment to the Paris Climate Agreement through the following actions:[6]

- Collect data on non-national climate action to quantify and report on progress made towards the US pledge (NationallyDetermined Contribution) under the Paris Agreement.

- Communicate the findings and results of our research and data collected from non-national actors to the international community and the United Nations.

- Catalyze further climate action in the near term by providing detailed roadmaps for similar business-level, city, and state action in the US and, potentially, in other countries around the world.

Beyond the rhetoric and lofty ideals of America’s Pledge, there are already efforts to step up the work of addressing climate change. For example, California environmental regulations earlier this year in March, that prohibits the use of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs),chemicals that are “between 1,000 and 3,000 times more potent than carbon dioxide”, and are emitted by air-conditioning and refrigeration units.[7] In addition, New York City has moved to divest billions of dollars in pension funds from the fossil fuel industry, directly challenging some of the biggest contributors to global warming like ExxonMobil, Chevron, and ConocoPhillips.[8] Although the current number of states and cities taking proactive measures to address climate change is small compared to the rest of the country, their actions signify meaningful progress, and create a framework for how state and city governments can carry on the work of addressing climate change, in accordance with the Paris climate agreement.

Just a few weeks ago, the U.S.climate change movement received an injection of life. With the victory ofDemocratic candidates in regaining the majority of the seats in the House ofRepresentatives, there is a possibility they will push the President andRepublican-controlled Senate to enact more environmentally-friendly policies.Speaker of the House of Representatives Nancy Pelosi committed to reviving a select committee focused on climate change.[9]

Furthermore, the private sector is making a slight pivot toward alternative energies. The advent of companies likeTesla have steered the conversation on economics and the environment to a place where intersectionality, and collaborations between diverse interests exists.Large American oil and gas companies are facing increasing pressure to follow the lead of European oil and gas companies to making investments in renewable energy technology in order to keep up with industry trends.

To be clear, honoring the U.S.’s original NDC commitment of 26% – 28%, as part of the Paris accords, would not have been a magic wand that would have solved a big part of global warming by itself. American consumerism, the powerful influence of oil and gas corporations in politics, and attitudes of American politicians towards climate change have been around long before Obama. They have, however, been compounded by the current administration of Trump, which has renounced the Paris Accords as part of a larger U.S. withdrawal from world affairs. As result, it is highly unlikely that the U.S. will keep to its NDC.

To everyone’s misfortune, climate change is not a bipartisan issue that both conservatives and liberals in the United States can both rally around. The real victims of this failure will not be political parties or wealthy billionaires, but rather marginalized communities and impoverished peoples. Yet there is hope, in the form of progressive elected officials and civil society committing themselves to stand in Trump’s place to lead the country’s climate change mitigation efforts, as well as emerging industrial trends that favor sustainability and renewable technologies.

Edgar Ortiz is a member of the Young Democrats of America (YDA). He serves as an elected officer on several local, state, and national caucuses, and currently works asa Research and Policy Analyst at the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy(LAANE).

[1] https://www.ucsusa.org/global-warming/science-and-impacts/science/each-countrys-share-of-co2.html#.W_ZTWehKg5s

[2] Ibid

[3] https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/sources-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[4] https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/en.atm.co2e.pc

[5] https://www.opensecrets.org/industries/indus.php?ind=E01

[6] https://www.americaspledgeonclimate.com/about/

[7] https://insideclimatenews.org/news/30032018/california-hfc-ban-short-lived-climate-pollutants-global-warming-refrigerators-air-conditioners

[8] https://www.apnews.com/c0e7b71262474f5bae5ae5caa0e4b7ec

[9] https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/07/us/politics/house-democrats-nancy-pelosi.html?module=inline