The People’s Republic of China is the second largest single economy in the world. Not just its GDP is impressive, but also Chinese growth rates outnumber almost every other economy in the world. There are Chinese cities – most of which you probably have never heard of – that are bigger than whole countries or regions in Europe, the Americas or the rest of Asia.

But let’s start at the very beginning: when talking about the Chinese political and economic system, experts cannot really agree on a mutual term. Some describe China as a “neo-imperialistic” country, others call it a “capitalist authoritarian” regime. It seems hard to grasp that an authoritarian-ruled country with a communist party in power is able to generate more growth over almost 35 years than every other country in the world. Especially the very idealistic Western decision-makers fail to understand that you always have to be one step ahead if you want to keep up with China. The recent fights over Huawei, the One Belt One Road initiative and the massive impact of the US-China trade war are just small implications on what might happen when China keeps growing and expanding outside its own borders.

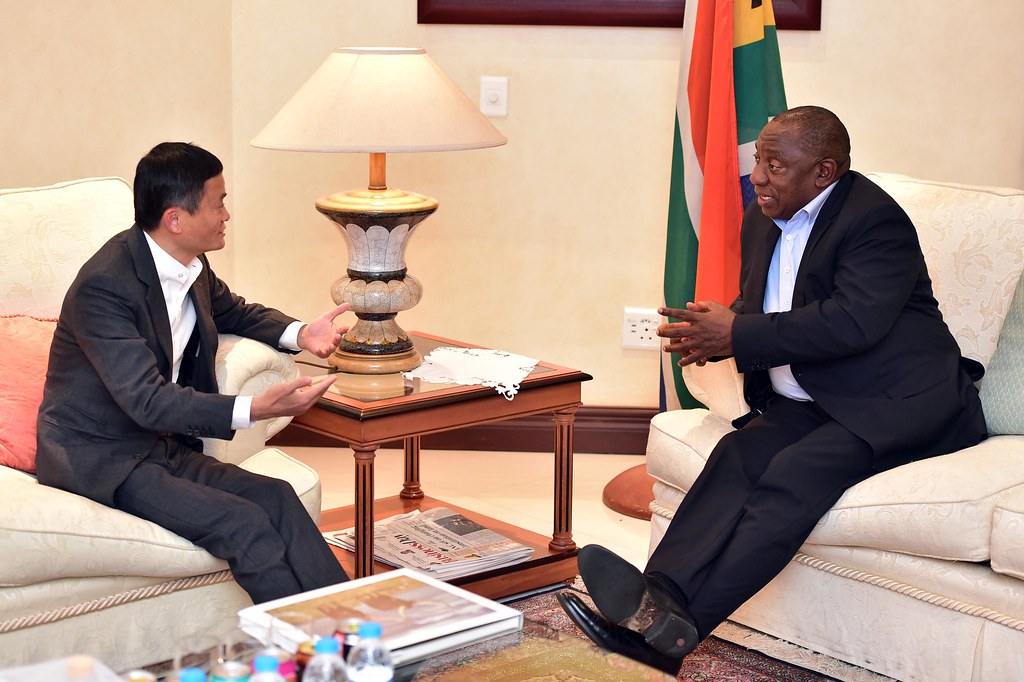

Africa for its part is certainly a continent that is heavily influenced by Chinese money. The involvement spans direct investments as well as state loans, trade relations and construction services. The latter is perhaps not very surprising as African infrastructure lacks reliability and modernity. But if you look deeper into the underlying agreements, you might get an idea why these investments could be problematic. From an outside perspective, China is just meeting the needs for African infrastructure investments. African countries – and not just those that are resource rich – show significant growth rates throughout the whole continent. But as the economy is growing faster than the basic grid of infrastructure, foreign investors seize the chance to expand their impact in those countries. Chinese construction contracts often include clauses that require African communities to buy certain Chinese goods and services, which obviously creates dependencies between both parties. Also, the employment of Chinese workers is part of these agreements, creating entire Chinese communities inside Africa. And this is where it becomes tricky.

Not just as liberals but as members of Western societies, we believe that our political system and the values we share are superior to those in autocratic or communist ruled countries. It is out of these obvious reasons that we condemn Chinese practices but, on the contrary, would support similar involvement of the EU or the USA. Human rights violations in China, the enormous limitation of freedom of speech, the involvement in Taiwan and Hong Kong and scandals regarding censorship and espionage are just a few examples why this condemnation is just right. But to avoid misconceptions of the applicability of our values in other parts of the world, we need to ask ourselves some very fundamental and partially provocative questions: does Africa really care where the money comes from? And should it be in our interest which ideology or regime might influence African development?

Whereas economies struggle in Europe and the Americas, African countries perform way above average. Still, private investors hesitate to take a closer look at the African continent. Until we are not able to mobilize private capital, we inevitably have to answer the above asked questions. For this, we need to overcome the widely spread narrative of “foreign aid” and focus on cooperation with African countries instead of a priori limiting the opportunities. This is the absolute condition for Africa to develop freely and independently of outside ideologies.