In the past decade, Europe has seen it’s citizens become more vocal about the institutional nature of the EU. Next April a consultative referendum will be held in the Netherlands about the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement. Ruling political parties and mainstream media in both The Hague and Brussels have been quick to label the initiative as a populist measure. Doing away with it in this manner is not only unfounded, it also risks harming the positive aspects European integration has brought us. Those who dump unfounded skepticism & constructive criticism on one pile are neglecting the long-term effects such behaviour can have on the electorate.

Decision-makers would be wise to identify it as part of an ongoing development throughout the landscape of the EU’s member states. If doing so one can only come to one conclusion: unless Europe’s decision-makers actively addresses the voiced concerns and substantial reform takes place, the ideal of a prosperous European community may come in jeopardy in the years to come.

past & future referendums

In 2005 both Dutch & French voters blocked the implementation of a supranational constitution, despite the fact that all major parties and most major news outlets in these countries campaigned for a positive outcome. In both cases, voter turnouts were almost 40% higher than for the regular EU parliamentary elections a year before. Two years later European legislators passed most of the constitutions’ content in what is now known as the Lisbon Treaty.

In 2013 David Cameron promised to hold a referendum on the withdrawal of the UK from the EU, which will now be held in 2017 at the latest. In the mean time the British Government is negotiating alternative bi-lateral arrangements, such as handbrakes & opt-outs for individual issues. Interestingly Switzerland has a stake in the British outcome as well. Their referendum to reintroduce immigration quotas was accepted in 2014, while Swiss law gives the government up to 2017 to proceed with implementation.

Although the alpine state is not an EU member, it is a signatory to the Schengen Agreement allowing for free movement of persons. Brussels announced it would use legal force if implemented, but if Britain receives a handbrake on immigration the Swiss could demand the same. The issue is further complicated by another referendum to be held at the end of February, that would have the Swiss government deport foreigners when convicted of crimes.

Most recently the Icelandic parliament is considering a referendum on EU accession. This after the Icelandic government pulled out of negotiations 2015, favouring to remain EFTA member. The EU does not consider the countries’ application dissolved, as it does not legally recognize Iceland’s political termination as a formal procedural withdrawal.

Status-quoists continue to portray referendums that challenge the EU both directly and indirectly as a nuisance. Political hindrances propagated by the stereotypical ‘ignorant & illiterate masses’. This couldn’t however be further from the truth. A significant majority of European society, whether in EU countries or those closely intertwined by them, are asking themselves these questions. They are represented regardless of age group, each educational level or social standing.

trials, tribulations & public opinion

In the last half century the EU has always been irreproachable in it’s founding goal: harmonizing European trade. It is impossible to refute that the European countries, whether EU member states or not, have benefitted socioeconomically from this progress. The system regulating commerce has been tried, tested and has stood the test of time. The system that should be managing all the other new competences that Brussels has taken on, not so much.

The debate around the EU constitutional referendum was one of principle, questioning the newly minted powers of Europe and possible hints toward federalism. The economic crisis and it’s subsequent fallout however, was the first tangible insight on the effectiveness of a political union. Greece was saved from bankruptcy, but not after months of debating & negotiating. How was such a fragile economy able to join the eurozone in the first place? How could Europe guard itself from devaluation if this were to happen again in the future?

If it took such a long time to come to an agreement, what could the effectiveness of other consent-based measures be? Having an EU rapid reaction force for example. Battalion-sized military units provided by member states, on standby, deployable within 10 days. All well and good, but it would probably take months to come to a decision to deploy them. National governments might as well just take the initiatives on their own, as France did recently sending peacekeepers to Mali or the UK sending trainers to Ukraine.

As if the economic consequences were not enough on Athens’ plate, the current migrant crisis presented itself. Aside from the responsibility national governments have to facilitate asylum procedures, maintaining external border security is a a self-evident example of a Schengen problem. The inherent failure of the European Commission to take responsibility for it has only helped to further weaken the public’s trust of EU leadership.

the Dutch referendum on the Ukraine-EU Association Agreement

In order to understand the motivations behind & societal support for the Dutch referendum on the EU-Ukraine Association Agreement, one must remove a vital element in the debate: the subject matter itself. Many see the referendum as a chance to voice the aforementioned discontents toward the EU as an institution, rather than a resentment against Ukraine directly. The underlying question is why the EU would negotiate a treaty that could impose far-reaching geopolitical consequences, without consulting the member states.

An analysis of public perception in the Netherlands shows a whole different dynamic than what can be distilled from written or televised media. From the latter one would conclude the debate is between stereotypes: ‘the educated cosmopolitans’ vs. the ‘illiterate underbelly’. The reality is that these groups are just trivial minorities in terms of the larger electorate.

The majority of the Dutch population could be described as cautiously progressive: supporting further EU integration on issues if that will yield a socioeconomic benefit to society, if they be managed competently & transparently and if based on the recognition of national sovereignty. What use is it to vote for a European Parliament, if ‘your’ EP representatives don’t hold ultimate legislative power?

Dutch voter turnout for the last national elections was 74.57%; the last European Parliamentary elections a mere 37.32%. Now consider from the total amount of votes, 6.12% went to parties that did not manage to win a seat due to the EP election threshold. Theoretically our parliamentarians derived their democratic mandate from under 1/3rd of the electorate. (Not bad considering other countries: 21.02% of the Slovakian votes didn’t get a seat and with a voter turnout of 13.05% that means their parliamentarians derived their mandate from just over 1/10th of the electorate.)

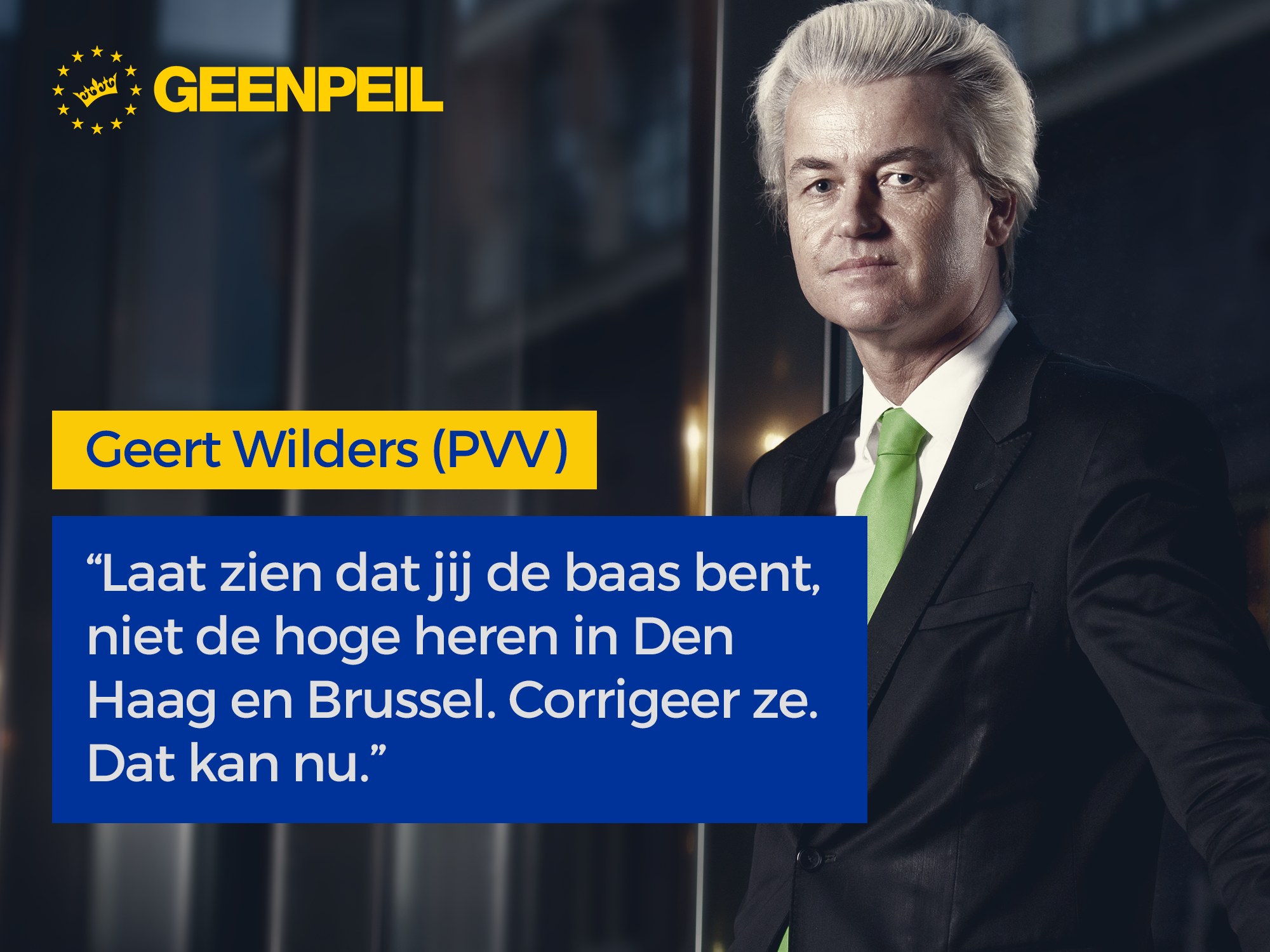

The Netherlands is one of the six founding members of what is now the European Union. It relies heavily on trade, predominantly with European countries, and is therefore intrinsically interwoven in the Community fabric. On the other hand there is a growing feeling of alienation from what the supranational organization has become. How else can one explain that Geenpeil (a collective of two pro-democracy think tanks and political satire blog ‘Geenstijl’) managed to get enough signatures within a matter of weeks to hold a referendum?

It may sound strange at first instance, but a ‘Geenstijler’ could sarcastically argue that faraway Kiev is closer to Amsterdam than Brussels is. Sure, you would be pointed out that Ukraine is a ‘corrupt oligarchy’ involved in a ‘raging civil war’ and ‘teetering on the brink of bankruptcy’. But at least decision-making occurs in the Ukrainian parliament. At least one can amuse oneself with Youtube videos of parliamentarians’ shouting matches and fistfights in the Rada. Failed state or not, at least the leadership has a tangible human factor. Unlike the ‘Brussels Institution’, the ‘Kiev Oligarchy’ one can identify the key players and their financial backers. Unlike Junker, Poroschenko let’s you know what you get: transparency, but probably not the kind you wanted.

The Dutch government, in face of both the sensitive issue regarding the MH17 aftermath and it’s presidency of the EU in 2016, decided not take an active public stance on the Association Agreement legislation at the start of the campaign. By limiting coverage of it in the national parliamentary debates, one could argue the referendum process was essentially facilitated by the government.

future developments

Doing away with negative public perceptions on the way ‘Brussels’ runs the EU as a mere ‘rise of populism’ or a ‘virus of euroscepticism’ is both misguided & dangerous. This reaction simply fuels the fires for populist fringe parties traditionally relying on the underbelly of society as their electorate. They are handed transformation into the mainstream on a silver platter, simply because the political establishment fail to pick up the issues at hand. Many average middle class citizens who may even support the idea of a transparent EU with independent legislative powers, who would never come out as supporters of right-wing flag-waving nationalist movements in public, are now more likely than ever to anonymously mark those boxes on their voting card in the many elections to come. Or simply stop showing up for EP elections all together.

To sum up, executive decision-makers in the EU should use the current European crises to their advantage, initiating bona fide proposals for change. Legitimizing Commission authority through direct elections, making it possible for citizens to vote for EP candidates from other countries, creating a rigid outline of national competences, holding fraudulent civil servants accountable for budgetary waste & intentional faulty expenses in national criminal courts rather than the EU’s internal administrative organs. All are just examples that could put an instantaneous halt to the growing discontent. More importantly it would regenerate societal commitment to the inspiring principles that the European Union set forth so many years ago. Down the road we might even see the Ukraine become a full fledged member of that Union. For the moment however, the outlook seems to remain status quo.

Ralph Aerts (1990) is a member of the Youth Organization Freedom & Democracy in the Netherlands. He is an Amsterdam-based legal scholar who liberally writes about current issues affecting the world around us.