This article is the introduction to a series by the IFLRY Climate Change Programme, looking at how different countries are implementing the Paris Agreement.

2018 is an important year for climate action and for IFLRY’s Climate Change Programme. This month, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released its Special Report predicting the consequences of Global Warming by 1.5C degrees. The report confirms that anthropogenic climate change is worsening and countries are drastically off track to advert climate impacts on ecosystems, human health, livelihoods, food security, water supply, human security and economic growth.

The timing for the IPCC couldn’t come at a more pressing time as countries convene this December to adopt the Paris Agreement Work Programme (PAWP) during the UN Climate Negotiations (COP24). The PAWP is the set of governing rules that will operationalize and bring to life the Paris Agreement. Getting these rules right is an imperative, considering that the world has less than 12 years to prevent dangerous destabilization of Earth’s climate, as outlined by the IPCC report. Countries are working overtime on crafting a final negotiating draft of the PAWP in time for COP24.

With all these important developments taking place, IFLRY’s Climate Change Programme is pleased to introduce the Climate Change Article Series in partnership with Libel.

The Climate Change article series looks at individual countries and how they are implementing the Paris Agreement in their national climate strategies. The series will look at countries’ commitments to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, referred to in the Paris Agreement as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and how these NDCs fit in with countries’ national climate plans. The series will also look at countries’ climate plans and how they interplay with the economy, energy consumption, and politics to identify challenges and opportunities to achieve the Paris Agreement goals.

Before looking at climate strategies it is important to look at what Nationally Determined Contributions are, how they differ between countries, and why they are the heart of the Paris Agreement.

What are Nationally Determined Contributions?

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are the engine of the Paris Agreement, as they represent each country’s efforts to reduce national emissions and to adapt to climate change taking into account domestic circumstances and capabilities. Under the Paris Agreement, countries must communicate, maintain and implement domestic policy measures to achieve their NDCs.

The aggregate of individual countries NDCs will determine whether the world will achieve the Pars Agreement’s long-term goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees with the aspirational goal of 1.5 degrees. Every five years there will be a global stock-take to assess the collective progress towards achieving the purpose of the agreement and to take more ambitious targets as required by science.

What type of NDCs are there?

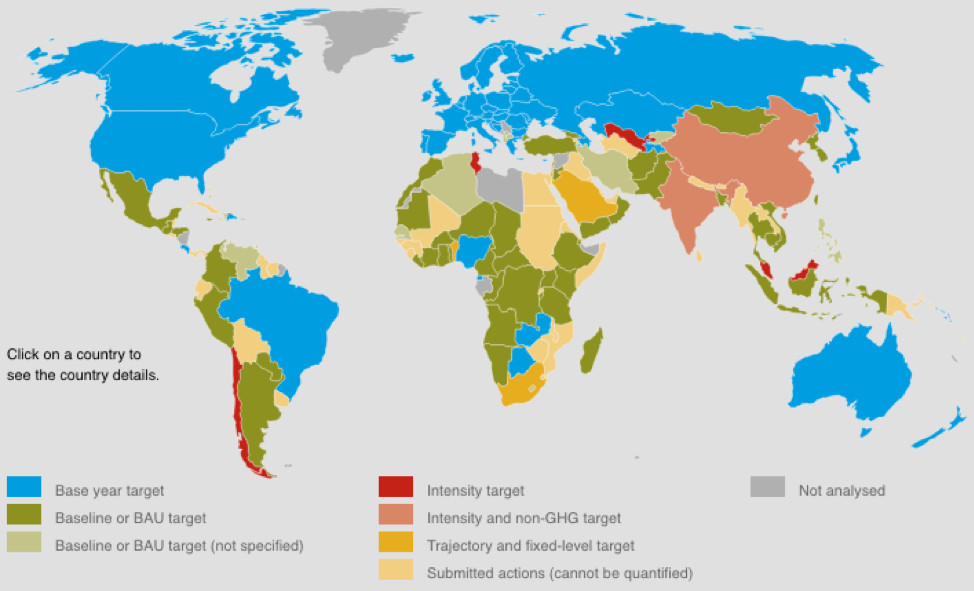

Countries must account their GHG emissions to track individual progress towards their mitigation NDC targets, track progress, and compare with other countries NDCs in order to assess collective progress towards the long-term mitigation goal of the Paris Agreement. Not every country measures the reduction of GHG emissions in the same way, what follows is an overview of the different kinds of targets different countries have set in their NDCs.

These are the type of NDCs used by countries:

(source: themasites.pbl.nl/climate-ndc-policies-tool/)

- Base year target: economy-wide absolute reduction from historical base year emissions. NDCs report on an absolute reduction from historical base year emissions. The base year chosen varies, with 1990, 2005 and 2010 being the most common. These NDCs targets are used by developed countries while developing countries are encouraged to eventually move towards adopting these set of targets as outlined in Article 4 of the Paris Agreement.

- Baseline or BAU target: emission reductions relative to a baseline or business-as-usual projection (specified in the NDCs/INDCs). The type of emission reduction relative to a baseline or business-as-usual projection has been chosen for many NDCs/INDCs, mainly for countries located in South America and Central America, Africa and South Asia. The mitigation component of the NDCs/INDCs specifies the business-as-usual emission projection.

- Baseline or BAU target (not specified): emission reductions relative to a baseline projection (not specified). Same as under point 2, but here, for the NDCs/INDCs, baseline or business-as-usual emission projections are not specified, such as for those of the Philippines and Venezuela.

- Intensity target. At least five countries, including Malaysia, in their NDCs/INDCs, indicate reductions in emission intensity in GDP as the main type of mitigation.

- Intensity and non-GHG target: emission intensity target and non-greenhouse gas target. China and India aim for emission intensity improvements, a target for non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption/power capacity, and for China, a target year for the peaking of emissions.

- Trajectory and fixed-level target. South Africa has a trajectory target stating the emission ranges for 2025 and 2030. Several countries, such as Israel and Ethiopia, put forward a fixed-level target, specifying the MtCO2e that they intend not to exceed in a given year.

- Submitted actions (cannot be quantified). Finally, many countries include mere qualitative descriptions of mitigation actions in their NDCs/INDCs, or specific targets for sub-sectors, such as for the implementation of renewable energy. As such targets complicate a precise quantification, we have not analyzed them here. This group of countries covers about 6% of the global emissions of 2010.

While the diversity in approaches allows for flexibility and consideration of countries’ national capabilities and contexts, a recent OECD report found that the diverse spectrum of NDCs and the wide range of developed and developing country capacities to implement accounting raise challenges for comparing and aggregating emissions. At the same time, having a more rigid and universal approach to NDC accounting raises challenges with regards to participation and inclusion of countries.

Why are NDCs so important?

The Paris Agreement has a bottom-up approach, which means that countries set their own climate targets as opposed to the Kyoto Protocol top-down approach that set a uniform set of targets. Although the Paris Agreement is a legally binding, emission reduction targets under the Paris Agreement are non-legally binding and essentially voluntary. Countries are responsible for setting their own targets and national strategies, but the ambition to meet those pledges are up to each country.

While this approach provides flexibility and adaptability to fit each country’s context, one of the challenges under this approach is with regards to the emissions gap. This means that pledges under the Nationally Determined Contributions so far only cover one third of the emissions needed, creating a “dangerous gap” as outlined in latest UNEP Emissions Gap Report and also noted in this UNFCCC communiqué ,and widely outlined in the latest IPCC report.

As stressed out by the IPCC report countries must take rapid and unprecedented collaborative and coordinated action if we are going to achieve a goal of 1.5 degrees warming. Addressing a complex challenge like climate change is not an easy task. Although the Paris Agreement has set a unified vision and framework for addressing climate change and a transition to a more efficient, low-carbon and climate resilient society, that vision won’t be achieved unless countries work together to meet their NDCs and increase ambition towards shifting to low carbon energy in a way that is just and fair for workers, communities, indigenous peoples, businesses and civil society.

It is our hope that the Climate Change Article Series will shed some light as to challenges and potential areas of opportunity to reduce countries’ emissions and achieve the collective goal of meeting global warming to 1.5°C degrees. By looking at countries’ commitments to reduce emissions, the CCP team will also acquire insights for IFLRY’s delegation to COP24 this December.

Perla Hernandez is a member and Co-Programme Manager of the Climate Change Programme. Perla is political science master’s student at Memorial University where she focuses on climate mitigation. She attended COP23 with IFLRY and COP18 as youth delegate. Contact: perlahg@mun.ca / Twitter: @Perla_hg