(Part 1)

In a great deal of European countries, the liberal parties of the 1970s acted as the first advocates of environmental protection – long before green parties took over their role with a new narrative. Sustainability has long been and must reemerge as a core value to liberals because the different pieces to it are unavoidably linked with each other: We cannot sustain the resources needed in business without keeping business within our planetary boundaries. And without proper business, we won’t even have the dry powder to sustain nature and healthy living standards in the first place.

Cost transparency as well as the polluter-pays principle set the foundation and success benchmark for climate policy around the world. However, they also mark the beginning and future of liberal involvement in it. In two parts, the author wants to outline how liberal thought contributed to environmentalism in economic thinking and eventually progressive policy action. It is time to reconcile liberalism with an opponent that has existed merely as a ghost in our minds.

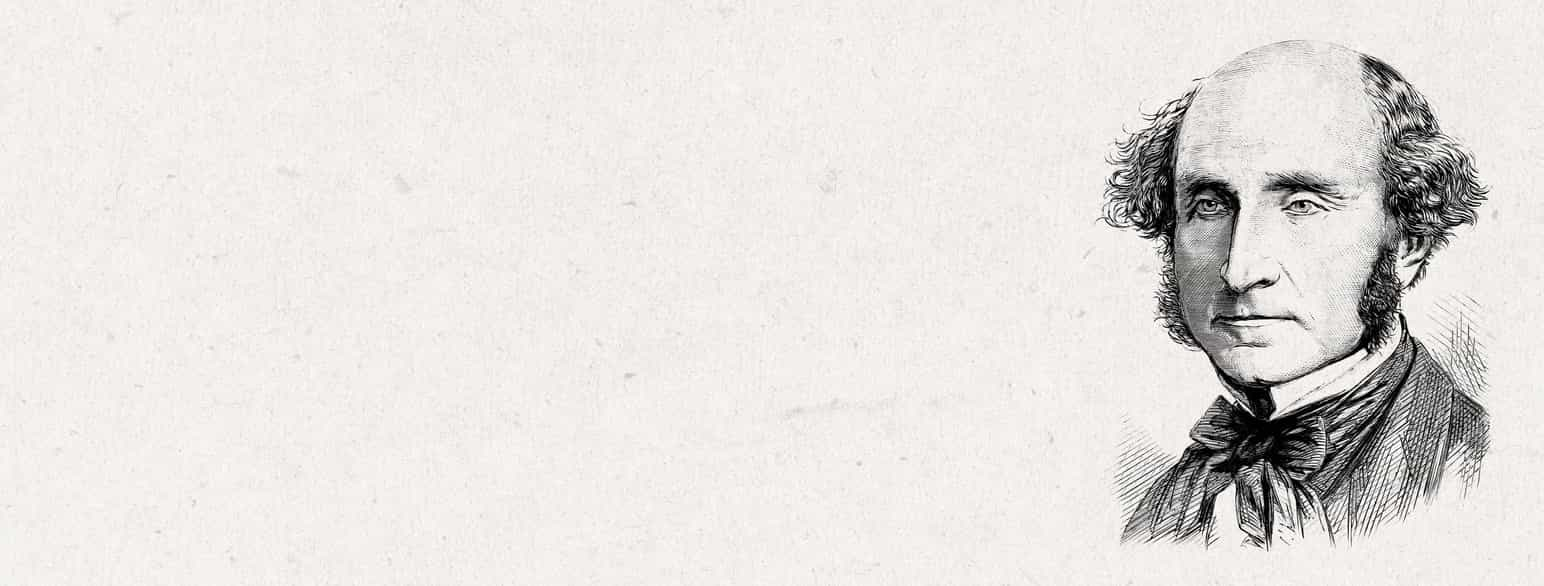

Mill: Resolving the Dilemma between Freedom and Failed Responsibility

The Brit John Stuart Mill, politician, philosopher and economist during the 19th century, is famous to liberals and libertarians around the world. He shaped what many of us think about liberalism with one quote:

The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good, in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impede their efforts to obtain it.

His thinking is an exemplary reflection of the Victorian Age. At a time when the world drew physically closer than ever before through industrialization, urbanization and global trade, Mill nailed it: to seize opportunities, where you don’t steal them from others, is the recipe for a thriving society with an entrepreneurial economy.

In essence, this marked the birth of “externalities” as a concept of economic theory. Whatever depletes the resources and hence abilities – present or future – of your peers, constitutes costs to society and requires compensation to be legit. Mill laid the groundwork for what was formalized later, in 1920, by his fellow compatriot and economist Arthur Cecil Pigou (although earlier concepts can be found in the oeuvre of Alfred Marshall).

Pigou developed Mill’s idea of accounting for failed responsibility towards inflicted bystanders of one’s actions with the idea of actually pricing and hence “internalizing” societal costs. To this date, the idea of a CO2 tax is labelled “Pigouvian tax” in his honor. And even if the tax aspect may repel many liberals as a questionably authoritarian policy instrument, Pigou’s thought pervades market theory deeply into the territory of conservative economists such as Gregory Mankiw, former advisor of U.S. president George W. Bush and founder of the “Pigou Club”.

Friedrich Hayek: The Inconvenient Truth of the Market Price

The probably most prominent figurehead of the libertarian Austrian School of Economic Thought, Friedrich August von Hayek, could not prevail against the father of modern economic policy, John Maynard Keynes, in an age of countless crises and disasters. However, his main idea caught on like a wildfire, influencing, among others, the marketing theory by Michael Eugene Porter as well as Jimmy Wales’ strategy behind his historic Wikipedia project: different from mainstream economic theory, we should see the price rather as the start than the end of the market dynamics. It is not a static scaling of supply and demand that settles a uniform price. Instead, a never-ending auction bidding among producers and consumers drives an evolutionary path until a stable price range is reached, according to the biologist’s son and passionate environmentalist:

The misconception that costs determined prices prevented economists for a long time from recognizing that it was prices which operated as the indispensable signals telling producers what costs it was worth expending on the production of the various commodities and services, and not the other way around.

For Hayek, the price of every good or asset is an indispensable information signal. Without it, investors would not be able to distinguish good from bad opportunities, buyers would waste resources on overpriced products and banks would lend money to doomed borrowers. This also leads us to Hayek’s most important political position: Socialism, propagating the total expropriation of business assets and consequently the disbandment of capital markets, would be bound to disaster if implemented. Adding value to anything becomes impossible if you don’t even know how valuable its components are.

It was also Hayek who brought the libertarian vision of decentralized economy and the need for compensation of environmental damage together in an add-on to his price theory:

Nor can certain harmful effects of deforestation, or of some methods of farming, or of the smoke and noise of factories, be confined to the owner of the property in question or to those who are willing to submit to the damage for an agreed compensation.

Are we living the “socialist nightmare”?

Surprisingly, to many of his fans, this ends in a radical conclusion for the problem of environmental destruction: if we do not compensate for them in the price we pay for assets, goods and services, our behavior towards nature since the Great Industrialization has been pure socialism. Hayek would turn around in his grave! Probably because he never got to elaborate on climate issues on a publicly known scale, too many libertarians and liberals around the world have been turning on full denial in the face of climate change.

After all, this is highly ironic and unnecessary, as liberalism provides us with the intellectual tools to grasp the problem. Hayek made a simple point from nothing more than real-life human behavior in economic decisions of when and why we, as markets, fail to consider the consequences of our actions. Mill and the neoclassical thinkers after him developed an almost independent concept for how market failure unfolds and how governments can remove the sand in the gears easily.