The implementation of the Affordable Care Act in 2010 (colloquially referred to as Obamacare) made mental and behavioral health treatment one of ten essential benefits required in new insurance policies sold on the federal health exchange. Despite this expanded coverage, however, many Americans still struggle to access mental health treatment because they are unable to afford it, lack proper resources, or avoid seeking care because of the stigma associated with mental disorders.

What’s worse is the far reaching evidence that suggests that the failure of the American mental health system has significantly contributed to the gross expansion of the prison population.

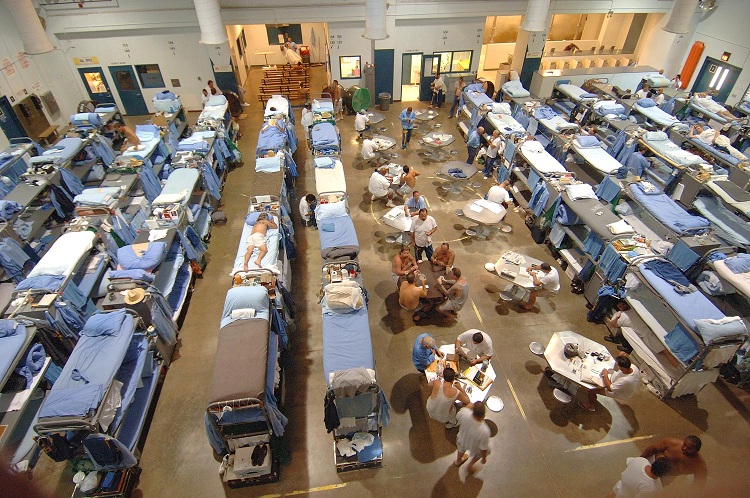

There are ten times more individuals suffering from serious mental disorders in American prisons and jails than there are in mental institutions – statistics which suggest that American prisons and jails have become virtual warehouses for the mentally ill.

The jarring 10-to-1 ratio is partially attributable to the decline of mental hospitals and asylums in the second half of the 20th century. But it also represents the correlation of incarceration becoming a favorable solution to treating mentally ill individuals.

Reports by Think Progress suggest there are just as many mentally ill individuals in prisons as there were in asylums decades ago. The difference here lies in the fact that prisons are less suited to treating individuals than asylums previously were. And as a result, mentally ill inmates leave prison significantly worse off than when they entered the criminal justice system. The impact is even more severe in the instances of juvenile incarceration, as studies indicate that putting young people behind bars is often the cause of mental health issues later in life.

The Treatment for Advocacy Center summarized the treatment of the mentally ill, juvenile and adult, in their 2014 report: “By shifting the venue of these mentally ill individuals from the hospitals to prisons and jails, we have succeeded in replicating the abysmal conditions of the past, but in a nonclinical setting whose fundamental purpose is not medical in nature.”

According to the report, 44 states and Washington D.C. have “at least on jail currently housing more people with mental illnesses than their largest state hospital does.” In recent years, states have cut back billions of dollars in spending from mental health funding. Meanwhile, use of psychiatric hospital beds have reached the lowest level since 1850.

But what does this say about American policy? Should there be more psychiatric beds or less prison beds? The answer, according to Doris A. Fuller, who co-authored the TRAC report,, is both, but only if the system is radically changed to prioritize rehabilitation and treatment, rather than isolation and punishment – as most mentally ill prisoners leave prison worse off than when they entered.

For mentally ill offenders, treatment outside of a cell wall is significant, and many would benefit from rehabilitation and other alternatives to incarceration. While psychiatric hospitals were often misused in their heyday, Fuller nonetheless contends that part of the solution to keep mentally ill offenders from becoming chronic inmates is to “make available more public psychiatric beds for those in crisis.”

This isn’t to say that mental health professionals are arguing for a return to an era where psychiatric beds are the default for mental health treatment – rather they would be used as the equivalent to the emergency room for people coping with serious mental disorders.

Fuller also notes that the authors of the study recommend that correctional facilities release mentally ill inmates with a discharge plan, which includes a discussion of how they will receive mental health treatment from a doctor in the community.

“This [practice] is barely used at all and there was one study of inmates released from prison without follow-up treatment,” Fuller notes. “They’re almost four times as likely to commit another violent crime compared to mentally ill inmates who leave prison or jail and get treatment. Why wouldn’t staying in treatment be part of their probation?”

Another effective solution would include expanding the use of Assisted Outpatient Treatment, a court-ordered outpatient treatment program which keeps people from entering the criminal justice system in the first place. AOT allows mentally ill individuals to live in the community–so long as they continue taking their medication.

Results from pilot programs have proven to be promising. As Mother Jones reports, a pilot project in Nevada County, California, cut jail time for mentally ill people in the program from 521 days to 17, and a North Carolina study of people in AOT found a reduction in arrests from 45 percent to 12 percent.

It’s clear that mental health care reform is necessary, and there are solutions readily available to be implemented, though in America’s political climate, change is slow going. Still, closing asylums without expanding mental health services in America has hardly lead to a more humane alternative.

“We closed the psychiatric hospital because we thought it was inhumane to house them in these hospitals,” Fuller told Think Progress. “But now we seem to have accepted as a society that it is totally humane to house them in jails and prisons. Are people really aware that this is what we’re doing.”

Danika is a musician from Northwestern U.S., who sometimes takes a 30 minute break from feminism to enjoy a tv show. You can follow her on twitter @sadwhitegrrl