Why the EU needs to step up its 2030 game:

In December, world leaders gathered at Le Bourget, Paris, for the UN climate negotiations, COP21. After both tense and intense negotiations, the international community managed to put together – for the first time in history – a binding and global treaty on climate change. The negotiations did not come without surprises, even positive ones. On the final straight of negotiations, a group of states – the “High Ambition Coalition” – emerged, advocating to push the previous temperature goal of limiting global warming to 2 degrees Celsius even further, to a more ambitious target of 1.5 degrees Celsius. This target had previously been perceived as politically unrealistic, albeit supported by science. But something happened in Pairs. Momentum was gained, and suddenly everyone – including previously sceptical parties such as the EU, USA and Australia – wanted to jump on board. In the end, the deal was sealed, with a 1.5 target and much appraisal. But what happens after the curtains have closed, the applause has faded and the crowd has left Le Bourget?

A temperature difference of only 0.5 C degrees may appear of negligible significance. However, it is crucial to understand is the difference between global mean temperature and local weather. Whereas the thermometer outside one’s window may shift from -30 C to +30 C throughout the seasons, the global mean temperature remains fairly stable. For instance, the last glacial period – the last Ice Age – came with a global mean temperature of only 5 C degrees below that of today. In comparison, due to greenhouse gas emissions caused by human activity, the global mean temperature is foreseen to rise by up to 4 – 6 C degrees by the end of this century in the business-as-usual scenario. This is not negligible. Such temperatures have never been experienced by mankind. Such a change would change life on earth as we know it. Such a change would, arguably, challenge the very future of our own species.

Climate policy is the greatest economic, social and moral challenge of our time. In order to succeed, climate change policy must mean economic policy, social policy and moral policy.

All’s well that ends well. But the Paris Agreement can only be seen as a starting point. The Paris Agreement has not, per se, resolved climate change. Climate policies are still made at national level, and the agreement is merely a tool for collective efforts. As the COP21 regretted to note, the national climate pledges submitted before the negotiations were not sufficient. According to UNEP, the combined pledges would only limit the rise in global warming to around 2.7 C degrees – way above the 2 C degree target set by previous COP negotiations, and almost double the target of 1.5 C degrees. Hence, increased efforts are very much needed.

The EU Council – the EU body representing the governments of the Member States – has welcomed the conclusions of the Paris Agreement, and has encouraged other countries to raise their bets. The Council has, however, been less vocal on the implications on the EU itself. EU has during the past decades portrayed itself as a frontrunner in climate policy, but just how well do the celebration speeches reflect reality?

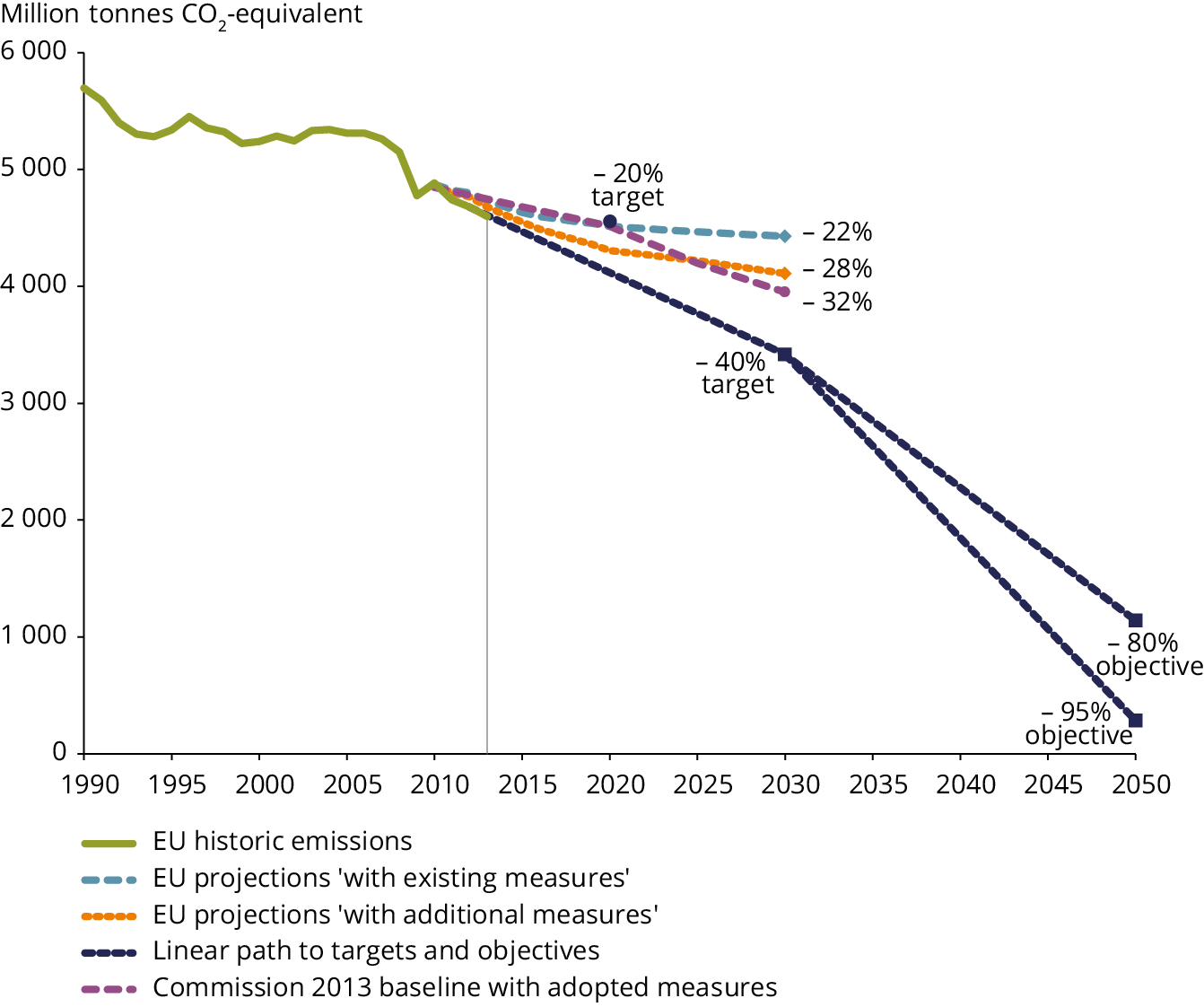

EU’s climate policy up until 2030 is based on a framework agreement made in 2014, setting an EU wide emission reduction target of at least 40 % to reach by 2030 (compared to 1990 levels). The same agreement includes a clause that calls for a reconsideration of the target after the Paris climate negotiations. These 2030 targets are to be viewed together with the EU long term goal of reducing emissions by 80-95 % by 2050 (compared to 1990 levels), as outlined in the 2011 Energy Roadmap.

In February 2016, the EU Commission communicated its COP21 review to the Member States, however, with no indication of wanting to raise the level of ambition before 2030. Meanwhile, a number of Member States, as well as several stakeholders within civil society and the business sector, have advocated for raising the ambitions.

Staying on track towards a 1.5 target requires intensified measures, also by the EU. According to analyses, the 1.5 target would mean that the EU would need to be close to emissions free by the middle of the century (i.e. reaching the higher end of the 2050 target), whereas the current 2030 policies only barely are enough for the 2 C target projections. Reviewers of the emissions pledges have deemed EU’s climate policies only average, whereas, proportionally speaking, countries such as Morocco and Ethiopia have much higher ambitions. In fact, EU overshot its 2020 emissions target already in 2014, six years ahead of schedule, despite an ineffective emissions trade system. Between 1990 and 2014, EU decreased its emissions by 23 %, while its economy grew by 46 %. According to Commission projections, emission reduction will reach 30 % by 2030 only with the Member State policies currently planned. Perhaps raising the bar should not be too unreasonable a thought.

Politically speaking, climate policies aren’t easy, rather, they are much easier to postpone. The decades it took to reach the Paris Agreement is perhaps the ultimate example of this. Yet, not making a political decision is also a political decision, and does come with political consequences. This is why postponing EU climate efforts to after 2030 doesn’t come without a catch. In other words, if we do the math: The current 2030 target only requires additional efforts equivalent to a 10 % emissions reduction during a 14 year period. From there, reaching the upper end of the 2050 target (as needed for the 1.5 projection) would require further measures equivalent to a 55 % emissions reduction during a 20 year period. It doesn’t take a mathematician to see that the equation comes with a great deal of what some would call optimism, and others would call passing on quite a workload – and price tag – to the following generations.

Responsible climate policy-making shouldn’t depend upon deus ex machina, neither should it place an unproportionate burden on the youth and future generations. The EU can, and should, step up its game and continue to show climate leadership. After the Paris Agreement, credible and ambitious politics must follow. Thus, the EU’s 2030 targets should, in line with the 2014 decision, be adjusted to be linear to the 1.5 C target, and the long term goal should be specified to the upper end. Climate policy must be reflected in general politics, in the EU emissions trade system reform and in financial flows. Paris was a milestone, but in itself not enough – climate policy can not only be rhetoric and speeches, but requires concrete action and leadership.

Anna Abrahamsson is Secretary General of Swedish Youth, Finland. She is studies International Public Law and is a member of the IFLRY Climate Change Programme.