Find Luke‘s other articles On Brussels here

After the UK’s departure a year ago, the EU hoped that then would be the time for a period of reflection, of soul-searching and potentially even reform. But a pandemic, economic crises, a belligerent UK government, an isolationist United States and political crises in Belarus and Israel dashed those hopes. Now, with the United States about to begin rebuilding its reputation in the world, the UK having fully completed Brexit and multiple vaccines being delivered en masse across the bloc, there is once again hope for a new, improved EU.

On 27 December, many member states, from Germany to Romania, began vaccinating their most vulnerable people in droves. Germany and Italy in particular have been praised for the speed and scale of their vaccination programmes. But, in a race against the clock such as this, there was always inevitably going to be scathing criticism.

Much of this has been directed at two members in particular: France and Sweden. On 5 January, it emerged that, in the first week of vaccinations, France had vaccinated a mere 516 people. At that pace, it would take around 3000 years to vaccinate the entire French populous. Considering that France is a major hotspot that appears unable to successfully contain the virus without tight restrictions, lockdowns and curfews, this news has been met with widespread derision across the world.

Towards Sweden, the criticisms are of a very different nature. Sweden has been vaccinating people at a good pace. But it is Stockholm’s strategy for dealing with the virus that has drawn ire. At no point during this crisis has Sweden been in lockdown. In fact, there have never been any major restrictions or quarantine requirements in place – only recommendations issued by Folkhälsomyndigheten, the Swedish public health agency.

The Nordic nation of around 10 million has recorded more than 500,000 cases and over 10,000 deaths – among the very worst per capita rates in the world. These deaths have disproportionately been in care homes. Now that Covid-19 is spreading like wildfire across Sweden – compounded by the presence of the hyper-infectious UK variant of the virus – the Swedish government is being sharply criticised the world over.

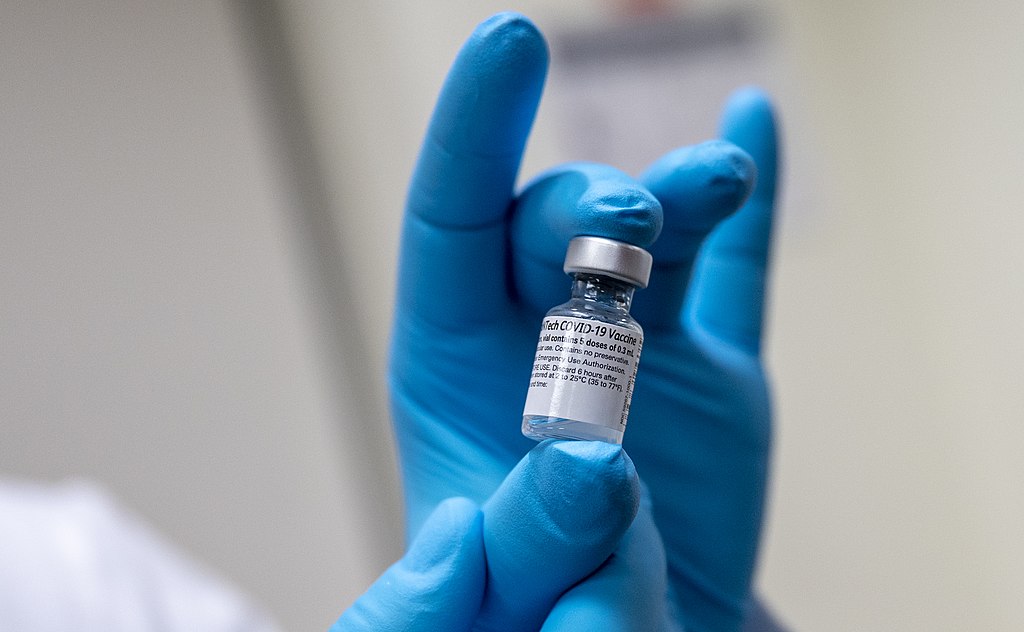

But the situations in France and Sweden were largely eclipsed on 15 January. On that day, it emerged that the production and distribution of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine – the one most widely in use currently – was going to be scaled back effective immediately. Both companies justified the move as being necessary in order to meet growing demand for vaccines in North America and the developing world. Be that as it may, Brussels took a dim view of the news, to say the least.

The EU, alongside the United States, is the global epicentre of the virus, as things stand. The only way for Brussels – and Washington DC, for that matter – to rid itself of this dubious distinction is to jab its way out. The EU needs to approach a critical mass of vaccinated people before the pandemic in the bloc can begin to come to an end.

Throughout this crisis, the EU’s image has been battered mercilessly. Despite this, unity amongst the EU27 leaders – even between the likes of Luxembourg and Hungary – has mostly held firm. But now, unintentionally, Brussels may have set another challenge to its unity – this time, one on the other side of the world.

Recently, the EU has set about beefing up its trade relations with China – despite its actions towards Hong Kong and its systematic ethnic cleansing against the Uighur minority in the north of the country.

On 30 December, just days after the EU had struck a post-Brexit trade deal with the UK, it struck a deal governing bilateral investments with China. The deal has caused even greater strain to Brussels’s already tested relations with Washington. The United States had been looking to its allies, including the EU, to present a united front against Beijing’s increasingly flagrant flouting of international norms.

The EU prides itself on being a family of twenty-seven nations united by common values of democracy and respect and promotion of human rights. In recent years, Poland and, in particular, Hungary have strained that. In fact, Brussels is now actively looking for ways to block funding to Budapest wherever possible – without needing the approval of the other twenty-six members, something that Poland simply will not grant.

It is not a great look for a bloc that is grappling with the retreat of democracy in Budapest and Warsaw to increase ties and strike a deal with Beijing. The deal has already drawn sharp criticism from the likes of Spain and Ireland. But, as it is a framework for investment only – affecting only the Single Market for Capital – national and regional parliaments are unlikely to have the opportunity to accept or reject the deal. That being said, there is opposition from MEPS, who will have to ratify the deal.

Amidst the chaos and death of the pandemic, it might well be that the EU-China investment deal simply flies under the radar. After all, the EU-UK post-Brexit trade deal was struck and conditionally ratified in December with little aplomb – outside of the UK, that is.

Brussels looked to 2020 for a period of reflection and renewal. Instead, it got a pandemic, economic crises and belligerent neighbours. With the vaccine being rolled out and a post-Brexit trade deal in place, 2021 looks set to be for the EU what 2020 was not. But, as its deal with Beijing ably shows, the EU needs to tread cautiously into this year.