In November the Junge Liberale (JuLis), IFLRY’s German member organisation, will celebrate their 40th anniversary. For Libel, this seemed like a good occasion to interview former JuLis member and former IFLRY president Imke Roebken. Imke was president of IFLRY from 1991 to 1997. In this interview we discuss how she became involved in politics, her years at IFLRY and the JuLis, the value of international youth politics and how her involvement has shaped her life and her career. The quotes in this article have been lightly edited for clarity.

Becoming a Liberal

Imke grew up in Hamburg, Germany. When she was young, her parents were members of the German liberal party Freie Demokatische Partei (FDP) for some years. This is what she remembers from that time:

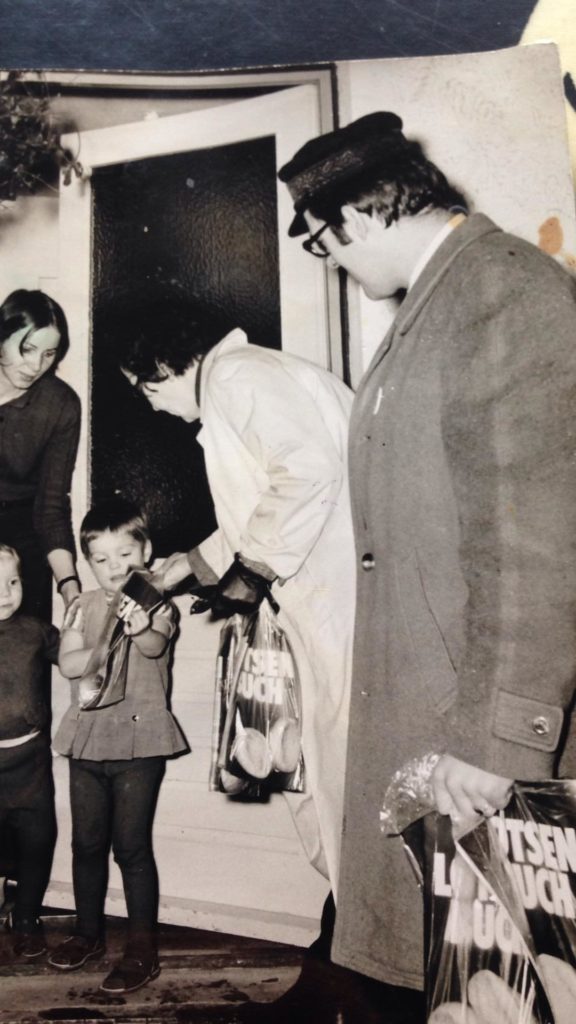

In 1972, when I was six years old, I was helping in the election campaign. We were distributing leaflets during an event with different parties. At that time, the FDP was in coalition with the Social Democrats. I didn’t understand really anything, but I understood that we were with the kids from the SPD and the kids from the Christian Democrats were not with us. I also have some photos of the FDP distributing bread rolls when I was much younger, that was maybe a regional election.

As a teenager she joined the Jungdemokraten — then the official youth organisation of the FDP. This is what she said about joining:

I wanted to contribute to democracy. In my family, the Nazi time was very important, especially on my mother’s side. They talked about it. Most Germans of their generation wouldn’t — I mean younger people later spoke about it, of course, in the 70s and 80s, but that was often not personal. My grandmother’s father, luckily according to her, died in May ’33 of a heart attack, otherwise he would have had problems, as he was politically active — his cousin got arrested and was sent to Buchenwald. She also had friends who, according to Nazi ideology, were Jewish or partly Jewish, and I met those women also. For me the Nazi time was not as long ago as it maybe feels today for some.

I only realized some years ago how special that was, because most people seem to say that their family was not involved. My grandmother felt very sorry and sad that she had not been able to do much when she saw the deportation trains riding through her city. She was showing me the place from where she saw those trains. Her friend from the sports club was the last one to get married in the synagogue of her city before it got destroyed. Luckily she could escape to Uruguay.

At fifteen or sixteen, I felt that it was — for me — an obligation to contribute to a democratic society and to freedom, and these are still the most important values for me. I think the liberals were then, and still are, the best to defend human rights, democracy and freedom. That never changed in my political convictions. That is why I joined the liberals.

In 1982, soon after Imke joined the Jungdemokraten, the youth organization severed its ties with the FDP. The FDP and the Jungdemokraten had long been drifting apart, because the Jungdemokraten had been taking a more left-wing stance, whereas the FDP had become more centre-right / economically liberal in its approach. At the time, Imke stayed with the Jungdemokraten.

When I started to be active in politics, the Jungdemokraten were the official youth organization of the FDP. In Hamburg they were not as left-wing as in other regions, where they believed in the theory of state monopoly capitalism. The JuLis back then appeared to me like the boys in my school who were speculating on the stock exchange and running around with briefcases and that was not appealing to me. But later, things changed, I met different JuLis, the Jungdemokraten changed more to the left also. It might all sound complicated today, but I have to tell you that is how I started.

This is what she had to say about her first involvement with IFLRY:

My first IFRLY event was a summer camp in Greece in ’84. From that moment I took any opportunity I had to be involved in international work. For some time, I also worked in one of the international committees of the National Youth Council and participated in many bilateral exchanges the Jungdemokraten took part in; for example with GDR, Hungary, Romania, the Sovietunion and Poland, where I visited Auschwitz in 1986.

My first IFLRY seminars were seminars in Denmark, Sweden and in Strasbourg I think. The seminars in Strasbourg used to be one week long. I thought they were really great, because you had time to discuss things in depth and to get to know people really well. The cooperation with a tutor and simultaneous translation in the European Youth centre also helped.

At some point I became the international officer, so I represented the Jungdemokraten in IFLRY’s executive committee, which met twice a year. In the executive committee each member organization had one representative. In the general assembly each member organisation had a delegation according to their size.

In 1985, the JuLis applied for candidate membership to IFLRY, a preliminary step to becoming a full-fledged member organisation. This is what Imke remembers about that:

When the JuLis became candidate or full members of IFLRY in ’85 at a congress in Dordrecht in the Netherlands, as always the other member organisations from the same country were asked what they thought about the organisation joining. So I think the first thing I ever said in a plenary session of an IFLRY general Assembly was that the Jungdemokraten supported the application of the JuLis because: “Diversity is beautiful.”, which was a IFLRY slogan at the time. I still like that slogan and think it is more meaningful than one might thing at a first glance.

Eventually Imke became one of IFLRY’s vice presidents in 1989, then IFLRY’s president in 1991 and later joined the JuLis.

I got elected to the IFLRY’s bureau as vice president for the Jungdemokraten in a very rainy Portugal in 1989. After I had been on the bureau for two years, I was going to run for President. The international officer of the JuLis asked me if I didn’t want to join them, finally and that is what I did. I then was then President of IFLRY for six years.

The Value of International Cooperation

When we asked what attracted her to international work, Imke said the following:

I don’t know exactly. It was maybe linked to the beginning of my political involvement and it was an opportunity that came up with the event in Greece and other seminars and exchanges. I went there and I realized that’s really something that I liked and got a lot out of, and that I could contribute to. To me it was great to be able to meet young liberals from so many different countries.

It was also related to democracy, and wanting to promote human rights, democracy and international understanding. I strongly believe that contacts among young people are very important to improve international and bilateral relations, one example of this could the French-German youth office and also I think that Dutch-German relations have improved since I started to be active in international youth work. I believe what you are doing today in IFLRY and LYMEC hasn’t lost relevance. If you meet other young liberals you have a common basis and you have a common interests in what you want to talk about and achieve together. This you do not get by just travelling. And you meet people from very different backgrounds you might never meet in your own country. I remember the day I met some young people from the UK in the European Centre, who had never travelled abroad before and also in different countries young liberals had very different social backgrounds. So I think IFLRY leads to a unique and fascinating kind of exchange in which we share common liberal values.

East-West Relations

Our discussion of Imke’s time at IFLRY Bureau began with the subject of East-West relations. In 1989 she was actually at a conference in Prague, then Czechoslovakia, when protests against the communist regime erupted:

After ’89 – that was one of the defining moments – I was, by accident, in a meeting in Prague when the Velvet Revolution started. The first demonstrations were on Wenceslas Square. To see something like that, you get a different understanding for it or feeling for it than if you are just reading about it in the media. I grew up with the idea that the Berlin wall and the Soviet Union would be there for ever, or at least a very long time.

It must have been the 17th November of ’89. It was the first evening people were assembling on Wenceslas Square and we had been there for a — by then really outdated — East-West conference. We stayed a day longer, and demonstrations started to happen. And then after those events in ’89 it was of course fascinating to see all the new liberal youth organizations and parties in Central and Eastern Europe develop. IFLRY quickly had contacts and subsequently members in Slovenia, Croatia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Lithuania etc. Some of those changed names, political direction or disappeared altogether so there was a lot of work, but it was definitely a fascinating time.

Although by that time it was clear that these East-West youth conferences were outdated and they ended in 1990, we couldn’t help but ask what they were like before it was clear that communism was collapsing. This is wat Imke had to say:

They were part of the policy of détente with the East and it was called the All European Youth and Students Cooperation (AESYC). Almost everyone participated in them, the umbrella organization of the Socialists, IFLRY and by then also the Christian Democrats and even the Conservatives as observers. Also the European organisation of national youth councils (CENYC) and the European Jewish Students participated. The initial starting point was to allow for human contact and to work for peace and the implementation of the Helsinki baskets. Some events were thematical others were sort of Assemblies called Consultative meetings where policy statements were adopted after endless negotiations. Often it was quite interesting and you definitely learnt to draft and defend documents and to negotiate even if sometimes the seminar as such was boring. I remember an IFLRY delegation to an event in Magdeburg about “Concrete Proposals for the Nuclear, Chemical and Conventional Disarmament in Europe” that was really not exciting at least for me! But this was mostly before my time as a bureau member.

Democratisation in Latin America, Expansion into Africa and Asia

Of course the work with new liberal forces in Central and Eastern Europe were not the only thing IFLRY was working on during Imke’s time on the Bureau and subsequently as president.

We had one general assembly each year, but only every two years there were elections. We had two executive committees, as I already said. And I think we had three to four regular seminars, and then extra seminars if we got funding from organisations like the Friedrich Naumann Foundation. Sometimes we also had study visits. We more or less tried to organise study visits to all the first free elections in Central and Eastern Europe. IFLRY also worked a lot in the European youth structures, which were also very different from what they were today. And we were very active in the Council of Europe Youth Directorate, I was member of the Governing Board for some time, and we had very active contacts with the liberal group in the Council of Europe. We were of course also active in Liberal International. I think I was the first IFLRY president that was also vice-president of Liberal International, also thanks to former IFLRY president Jules Maaten being LI Secretary General then.

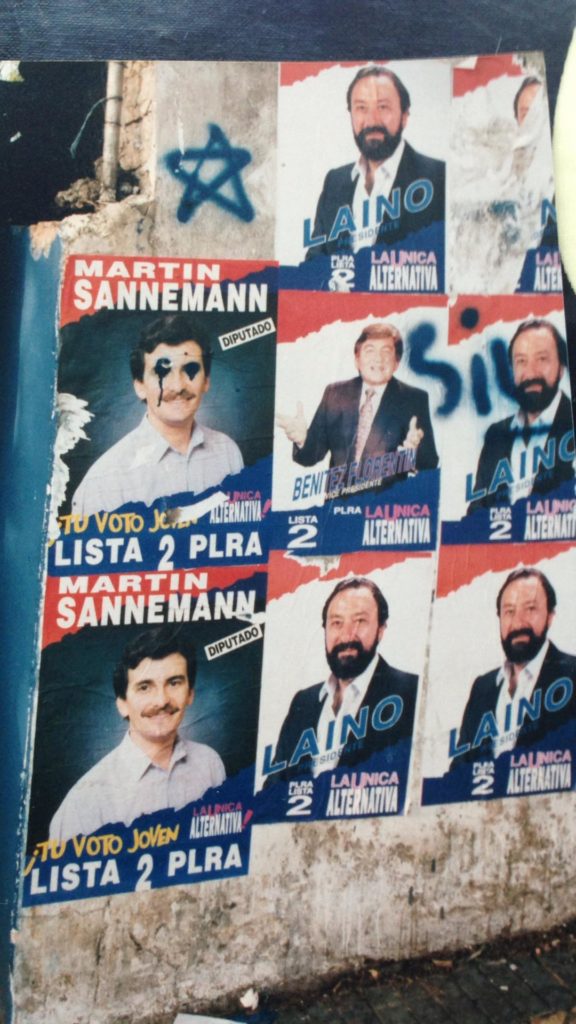

Besides that, we focused on democratisation in Latin America, which started before the end of the cold war, and became an important area of IFLRY activities. The first vice-president from Latin America, Martin Sannemann, was elected to the bureau also in 1989. He came from Paraguay where the main opposition party was liberal. He had been in exile in Germany and later had different government functions and became ambassador to the OAS in the US. IFLRY also had members in Chile, Uruguay, Argentina, Columbia and some other countries. In 1993 IFLRY organized a delegation to observe the elections in Paraguay, after Alfredo Stroessner had been finally ousted, but when the Colorados were still in power.

At the same time IFLRY was building up contacts with Africa and Asia.

It started around that time. I think the youth organisation of PDS in Senegal was the first full member organisation from Africa. There were also various parties that came and then disappeared again. The young liberals of the Philippines whom I think I first met in a seminar in Sintra, attended an IFLRY congress for the first time in 1990 in Budapest and the first Asian bureau member Chito Gascon came from the Philippines too. In the following years also organisations from other Asian countries attended IFLRY events.

There was really a lot of expansion. This was challenging for us, because our funding was mostly European based and came to large extend from the Council of Europe. With the expansion we had to pay for much more expensive travel tickets with the same amount of money. We also tried to have Spanish interpreters at the congresses, sometimes also French, so people could participate better. That was a lot of what we achieved at the beginning of the 90s. That people from these new countries could actually participate and join. Together with the expansion to Central and Eastern Europe. Now you have congresses all over the world — I don’t know how you finance them. But in my time, we weren’t able to do that. The only General Assembly outside Europe took place in Israel in 1996 I think. We would always try to combine conferences with a seminar not too far away from the congress venue, so we could make sure that each member organisation could send at least one delegate.

Observing Elections in Paraguay

When we asked Imke whether she took part in the various study visits and election observations she said:

I always tried to send the people on the bureau who were responsible for the region. Actually, that was a good example of intercultural communication. At one point a delegate from an African country was very annoyed that I, as president, didn’t come to his country. Because they thought that meant that I didn’t care about Africa. But I thought it was more democratic for the person on the bureau who was responsible for Africa to go. But we got a lot of funding to go to Paraguay, so I was able to go there. I also participated in Liberal International delegations and many events of the European youth structures in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in the countries that formerly belonged to Soviet Union.

We then asked her what it had been like in Paraguay.

The candidate of the liberal party didn’t win. There was still election falsification. We were helping the young liberals in the campaign two weeks before. Because Paraguay was such an isolated country during the dictatorship it was useful for them to have international people there. For us it was fascinating to see such a big liberal party! We were also trying to observe the elections in the polling stations, but the elections were still manipulated in the media, and I think also by the way they were counting the votes. So the liberals didn’t win yet, but it was the first election that really marked the end of the dictatorship in Paraguay. We saw similar election fraud in some places in the former Soviet Union. The people running the polling station had been told to fill in 50 election papers which they then folded in one pile. This you see clearly when the ballot boxes are opened.

International Cooperation before the Internet

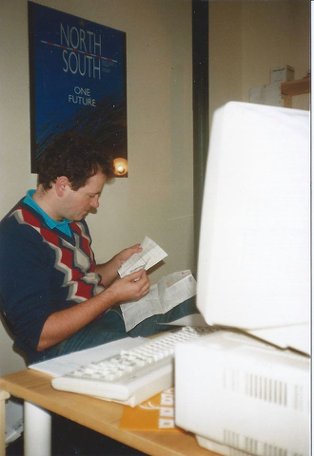

There was one big difference between international work then and now: the internet. Although IFLRY did go digital during Imke’s time as president (although of course this was before social media and internet calls), for a lot of the time in which she was active, communication had to be done the old-fashioned way. When we asked her about it, she had this to say:

That is actually what I was thinking today: how can they stay in touch with all these people from all these countries and finance it. And then I realised it’s a great advantage to have the possibility to do things online. After ’89 you could spend three days to send a fax to somewhere in Central and Eastern Europe, with an invitation for a conference, and it wouldn’t get through. Nowadays even e-mail is outdated: you can talk. So that was very different. We had to do almost everything by post and sometimes even the mail from Brussels to the Netherlands would take four weeks.

I remembered I called the president of the Slovenian youth organisation Roman Jakic (who later became foreign minister) during the Yugoslav Wars in the 90s. He was sitting in a bunker — Slovenia was not so involved, but at the moment, the situation did not look so good. We wanted to phone him to express our support, but in order to do that I had to phone the Berlin phone office to register a phone call….. Phoning was also expensive and later when IFLRY had e-mail not all members and contacts had it.

Also, for seminar readers and background materials we depended on written material. I remember spending nights at copy machines…. The European Youth Centre had a great library I used a lot. In the beginning there was also less information to be found online. I remember when first going to Ukraine most detailed information I could really find online was material from quite right-wing Ukrainian groups in exile in Canada.

The JuLis’ involvement in IFLRY

Our discussion then moved on to the involvement of the JuLis in IFLRY:

The JuLis were very active internationally and very ready to contribute. While I was president the JuLis had high-level involvement. Because some organisations just send some local member, which is of course also very nice. But if you want the backing of an organisation — also the financial commitment — it’s also great if the board of the organisation is behind international work as well. I think that people like Guido Westerwelle and also Birgit Homburger as JuLis presidents afterwards knew about the international work and supported it.

The Power of Youth Politics and of the Liberal Family

After discussing the involvement of the JuLis during her time as IFLRY president, Imke mentioned that she had met quite a few people later in her career, who said that going to IFLRY events had had significant effects on their future careers.

Yes it’s like you say, they are small things but they are really important. I later met quite some people who only attended one or two IFLRY seminars, and they still felt that those had an impact on their views and life. I remember a Swedish liberal who became involved with Human Rights issues in Cuba and started to work for the Swedish liberal foundation. And he thought this was because he attended one of IFLRY’s international seminars in Strasbourg. It’s small things like that, that hopefully matter and then make a difference.

To Imke, this was not the only benefit of youth politics and of the wider liberal network.

You share something. The belief in freedom and liberalism. Especially today, in some countries — or even I, in certain debates, in certain environments — you can feel quite lonely.

The left and the right often have – in my view – easy and simple sounding answers and little space is left for more moderate views. If I talk to liberal friends I do not have to first clarify that yes I also think the climate and racism are important issues if I want to express some doubts about how campaigns on those issues are done. I am not sure I want to say this in public but when there is group pressure in schools to attend the “Fridays for future” and there is back-up for this from teacher I have a problem with how the campaign is done. I don’t like it if activists think there is just one way to campaign and just one truth. And that people think that just to reach your goal you are allowed to use all means. For me the goal never justifies the means.

If I have to explain this to a friend who is not from a liberal background, I have to be very careful what I say, in order not to be misunderstood. I still really appreciate that amongst liberals, this is understood.

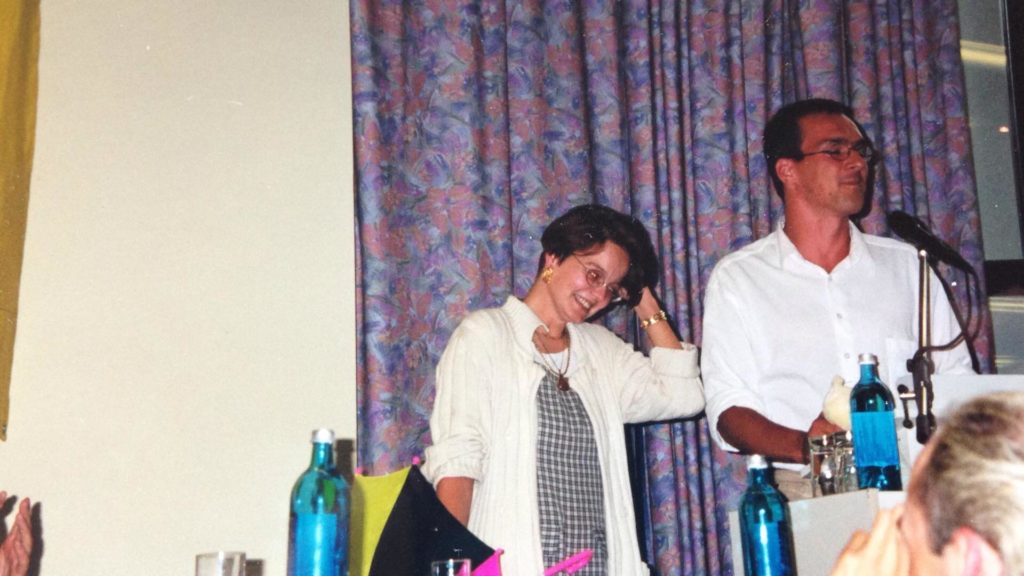

Finally, when we asked Imke what working for IFLRY had brought her, she had the following to say:

A lot. I don’t know what kind of person I would be without IFLRY and the international work. I would probably have ended up moving to another country anyway. But if you do this type of work for as long as I have, it influences you of course. You learn an enormous amount about how to communicate with people from very different places. You learn that sometimes they express themselves very differently, even though they could mean the same thing. Or that they and you think they mean the same thing, but they don’t actually. And you learn a lot about liberalism and politics in other countries. The way I view liberalism is highly influenced by my international youth work I think. We also learnt a lot of practical skills as in small organisation like IFLRY you do almost everything: you learn how to organise, how to write reports in different languages, how to apply for funding and keep accounts. At the time we also learnt how to convince different airlines by phone that the visas of seminar participants were alright and they should be allowed to board the plane and for sure to deal with the Belgian administration, Belgian post offices and what is totally useless today to deal with a great variety of uncooperative copy machines! And you make very different friends and contacts, some for life.

IFLRY changed or widened my understanding of liberalism and democracy. Visiting different non-democratic countries and meeting young liberals from those societies makes you understand the value of freedom and democracy even more. You see and feel that in a way it is a privilege that your vote is counted correctly. We had a vice-president from Paraguay who had been in exile in Germany. I was influenced by seeing people in Paraguay, in the dictatorship, who had to suffer because they weren’t allowed to vote. Meeting people from Azerbaijan, who were imprisoned because they protested for more freedom and more press freedom. It makes you understand the value of democracy even more when you meet people from non-democratic societies. I think that made me a better liberal, hopefully. Because it makes you better at arguing in favour of these principles. At the same time, I also believe that liberalism is the only way that the world can continue to develop. There is no other…

At this point one of us interjected, saying: No alternative?

[laughs] no alternative. I’m not sure when all other people will understand that, but I really think there is no alternative. In Germany, with the grand coalition, we see that. It is not really leading to the creation of politics where you address the problem of the future. But what is most important for me is that for liberals the goal does not justify the means and that only an open debate that does not see certain opinions as the absolute truth or one issue as more important than everything else can really address the problems we face. Last but not least for me liberals are most committed to democracy. Democracy is not only threatened by it its open enemies but also by those who do not defend it or take it for granted.

Larissa Saar is a member of the German Junge Liberale (JuLis), a Libel editor and member of IFLRY’s Climate Change Programme. She has recently graduated with a Master’s in International Peace Studies from Trinity College Dublin. You can contact her via email: larissa.saar@julis.de

Krijn van Eeden is editor of Libel. He grew up in the Netherlands, but moved out of the country at the age of 18. Currently, he is studying for an MA in Philosophy at the University of Frankfurt, Germany. Before that he lived in London, where he did his BA and subsequently worked for the Liberal Democrats.

1 comment