Find Luke‘s other articles On Brussels here.

In Paris, anger is palpable. In Oslo, the winds of change have reached the ballot box. In Brussels, the EU27 held their collective breath as Germany voted.

It’s been several weeks that have seen change come at breath-taking speed for the EU. But what does this mean for? Is this a happenstance cluster of change – or the beginning of post-pandemic change for the bloc?

On 15 September, the UK and the US announced a trilateral security pact with Australia: AUKUS. The two global powers will help Australia develop and build nuclear submarines. This will make Australia only the seventh country in the world to have such military capabilities. For Canberra and Washington, AUKUS represents a major stand against China and its efforts to expand its control in the South China Sea. For Westminster, it represents the opportunity to take a step back onto the world stage, following Brexit and a battering courtesy of the pandemic.

But in Beijing and, surprisingly, in Paris, AUKUS is being seen as, at best, a direct challenge and, at worst, a threat. In Beijing, there are fears that a nuclearised Australia could put China on the path to war with the US. In Paris, the anger stems from a loss of pride.

AUKUS directly undercuts a 2018 deal struck between Paris and Canberra. That deal would have seen France build nuclear submarines for Australia. What is heightening the anger in Paris is that Australia did not breathe a word about its negotiations with the US and the UK until they had been completed. The first time many French officials knew of the pact was when it was publicised in media reports.

In the race to nuclearise Australia, France has very publicly been smacked down.

The scale of the French backlash has surprised many, particularly in Washington. Paris took the almost unprecedented step amongst allies of recalling its ambassadors to Washington and Canberra. Humiliatingly for Westminster, Paris referred to the UK as a “third wheel” in the AUKUS deal. Its ire was pointed firmly at the US and Australia.

Paris has now sent its ambassadors back to Washington and Canberra, but quite how all of this will continue to play out remains to be seen.

But the AUKUS deal did provide the EU with a moment of strong, public solidarity, as member states lined up to support France’s position. As the whole debacle demonstrates, there is more overlap between the EU and NATO than many would care to admit. This strikes a troubling chord for those of the EU27 that are not NATO members: Sweden, Finland, Ireland, Cyprus and Austria.

But undertones also defined another important moment for the EU: the German federal election.

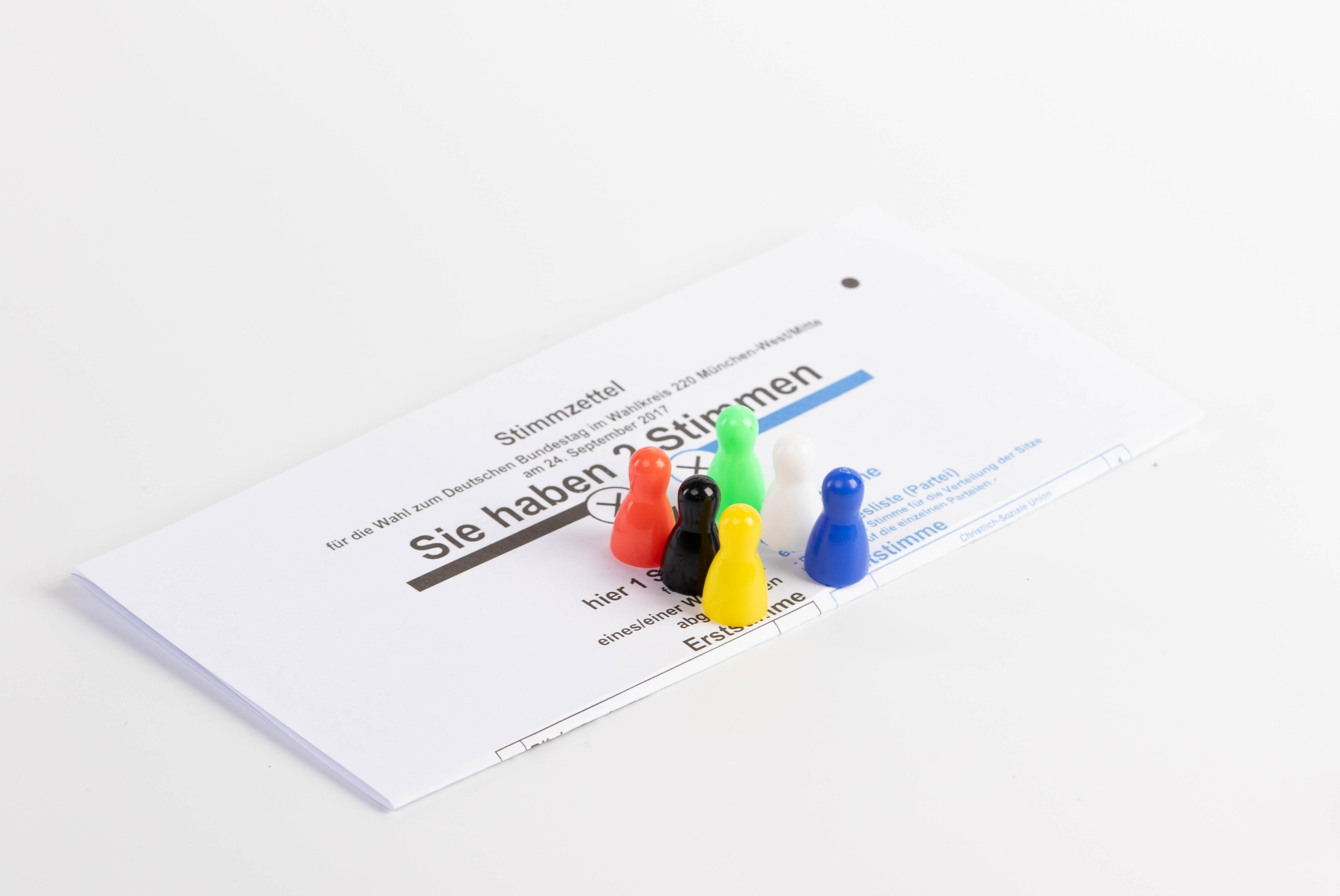

On 26 September, Germans voted to determine Angela Merkel’s successor. Among the longest-serving democratically-elected leaders in the world, Merkel’s sixteen-year tenure as chancellor is coming to an end – but it is not quite over yet.

After a long, tumultuous campaign, the election ended in a shift of power away from the centre-right CDU/CSU Union to the centre-left Social Democrats. With the Social Democrats only holding a narrow advantage over the CDU/CSU Union, the left-wing Greens and the centre-right Free Democratic Party will be the kingmakers in this new-look Bundestag.

Coalition talks will be long and complex, and will likely last until Christmas.

But, crucially for the EU, Germans backed the centre. The far-right Alternative for Germany and the far-left Linke both lost ground to the centre parties.

It was a similar story in Norway two weeks earlier, when Norwegian voters made Labour the largest party in the Storting, the Norwegian parliament. The centre-left, staunchly pro-EU Jonas Gahr Store is almost certain to become the next Prime Minister of Norway.

Whilst Norway is not technically part of the EU, it de facto operates within the bloc. It participates in the Single Market and is a member of the Schengen Area. Although Norway sends no formal representation to EU summits, this vote of confidence from Norwegian voters will not go unnoticed in Brussels. In fact, many in Brussels were likely hoping that German voters would follow Norway’s lead – and follow it, they did.

After two years of being battered by Brexit and the pandemic, those in Brussels might well be hoping that the elections in Germany and Norway might mark the beginning of the end for the wave of populism that swept the West from the mid-2010s onwards. With the EU standing united behind France with regards to AUKUS, there are tentative signs that the traditions of solidarity and unity are slowly returning.