New York City — the largest city in the United States, a global city if there ever was one, and home to over 8 million people — recently held its primary elections for municipal government. The general election is still not until this November, but in this overwhelmingly Democratic Party voting city, all political observers understand that the real contest for mayor, for city council, and for a variety of other municipal offices takes place here in the primaries.

This contest, held once every four years, would be significant enough in any year. This year, it took place amid the backdrop of New York City’s emergence from its most serious period of crisis in decades. At the beginning of the Covid pandemic, in March 2020, New York City quickly acquired the unwanted global distinction of being one of the worst hotspots for Covid anywhere in the world. A city whose economy is largely defined by industries like real estate, tourism, performing arts, and restaurants saw the sudden and prolonged shuttering of every public venue and the emptying out of the Manhattan business districts as office workers remained at home. The city’s unemployment rate reached nearly 20%. But far worse even than that was the direct human cost of the pandemic; over 30,000 New Yorkers, roughly 1 out of every 246, have died of Covid. Over 110,000, roughly 1 out of 74, have been hospitalized, and about 795,000, roughly 1 in 10, have had a confirmed case.

And then less than three months after the beginning of the Covid crisis, in May of 2020 the city exploded into another crisis: the massive protests following the murder of George Floyd by the police in Minnesota and the brutal and violent response by the police department, including the arrests of over 1,300 people in the span of one week in June 2020, which deeply polarized policing as a political issue at a time when some people perceive crime to be increasing.

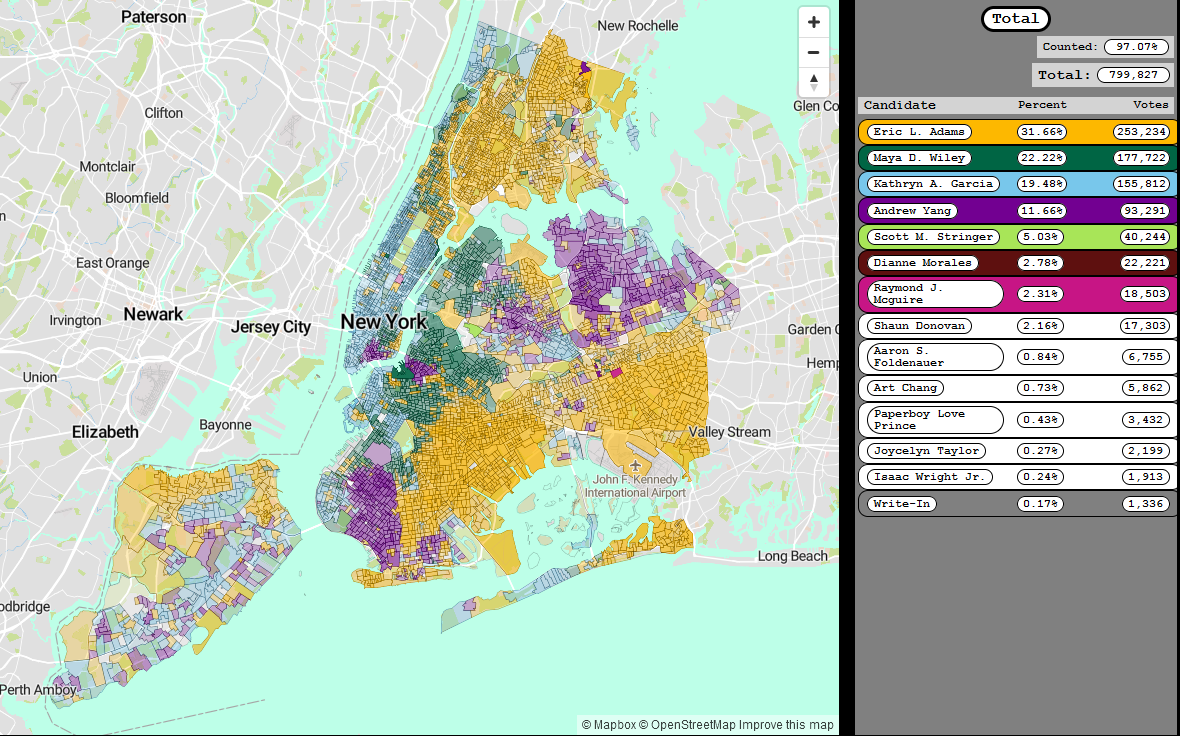

It is against this backdrop that New York set about choosing a new mayor, to replace the term-limited incumbent Bill De Blasio. Adding to the interest and significance of the contest was that it was performed using “ranked choice voting”, an instant-runoff system where voters are able to rank up to 5 candidates per contest in order of preference. In this system, the counting process then proceeds in rounds, with the lowest-polling candidate eliminated and their votes reallocated according to next preferences in the next round until a single candidate achieves a majority. While this system may be more familiar to voters in other parts of the world— Australia for example uses this system and calls it “preferential voting” — the 2021 New York City municipal election marked the largest-scale use of this system in an American election to date. Many observers speculated that this system would expand the field of candidates, since compared to the old first-past-the-post system, there was much less incentive for tactical voting and thus less pressure for candidates to be perceived by the public as viable. And while indeed, in the early part of the political campaign, there were nearly 20 declared candidates, and 13 candidates appeared on the ballot, only four candidates proved to be electorally significant once the votes were counted. (See title image)

The map of the first-round results of the election makes one thing abundantly clear to any observer: that New York City politics is polarized geographically. But because the city is also very racially and ethnically segregated by neighborhood, the geographic division correlates neatly with racial, ethnic, and social divisions. New York politics has in fact always been remarkably tribal and driven by ethnic affiliations, essentially since the beginning of the era of mass immigration in the mid-1800s. For much of the 20th century, the Democratic Party at the local level in New York, in order to maintain the loyalty of its various voter bases, followed an unwritten but strictly observed rule that out of the three citywide elected offices, today called Mayor, Public Advocate, and Comptroller, the Democratic Party nominees had to be one each of an Irishman, an Italian, and a Jew, reflecting some of the largest ethnic groups in the city. This rule remained in force basically until 1989 and the victory of New York’s first Black mayor, David Dinkens, in the Democratic Party primary, propelled by the rising electoral power of Black voters who were determined to bring new ethnic and racial groups into the mix of the city’s politics. Even to this day, it is impossible to discuss the competing political profiles of New York City politicians without discussing the social and demographic constituencies from which they derive their support.

Eric Adams, the Brooklyn Borough President, a former state legislator, and a former police officer with a history of unusual and controversial statements, staked out his political territory as the most conservative candidate with a message focused on being “tough on crime” and calling for more policing. At the same time though, Adams, who is Black, presented himself as a champion of the city’s large working class Black and Hispanic population, and followed an old fashioned New York political strategy of forming relationships with neighborhood and ethnic community political leaders with influence over their own constituencies in order to build a diverse coalition in support of his candidacy. The election results demonstrate the success of this strategy, as Adams was the overwhelming favorite in the large Black and Hispanic sections of the city.

Andrew Yang entered the mayor’s race as the political superstar. Yang was a political outsider who became famous in 2020 for his unconventional run for president in the Democratic primaries, centered around a national proposal for universal basic income. Feeling that he had made a name for himself and now had the opportunity to use his new fame to his benefit in a more serious attempt at political office, Yang decided to enter the mayor’s race. Despite early polling showing Yang as a strong frontrunner, he stumbled on the campaign trail as it became apparent that despite living in New York City, he was not familiar with local political issues or even with the structure and competencies of municipal government, and did not even have any history of voting in local elections. Especially for many of the city’s more highly educated voters, Yang’s candidacy came to be perceived as superficial and even insulting to the seriousness of the office. Despite early frontrunner status, Yang came in 4th place in the first round of voting on election day, drawing significant support only from a coalition of East Asian voters, and some of the more religiously traditional Jewish neighborhoods, a demographic Yang made an effort to court.

Yang and Adams developed a bitter rivalry between them in spite of, and because of, their shared appeal to the same side of New York City’s fundamental economic, social, and cultural divide. That is, they both directed their appeal as a more populist one, towards the middle and lower income, less highly educated and less culturally and politically progressive residents of what New Yorkers call “the outer boroughs”, the large swaths of the city outside the city center on the island of Manhattan, and in social and cultural sense excluding the western neighborhoods of Brooklyn and Queens close to the East River, and thus close in to Manhattan. On the other side of that divide, the results reflect the political dispossession of a social tribe, or really of two sub-tribes, which found themselves to be unexpectedly politically adrift until the closing days of the election.

The first of these sub-tribes is the high income and highly educated white voters who mainly populate the middle and southern portion of the island of Manhattan, in addition to a handful of small neighborhoods in the other boroughs, who comprise the economic and cultural elite of New York City. The political power of this “sub-tribe” generally exceeds their strength in numbers, firstly because these voters tend to be the most civically engaged — they are voters most likely to turn out and vote in otherwise low-participation elections, and secondly because they donate by far the most money to political candidates, in America’s political finance system where public funding is extremely limited and candidates must solicit private donations to fund their campaigns. Compared to the outer-borough voters who tended to support Adams and Yang, and who are often most influenced by the endorsements of local community leaders, including local Church and other religious leaders, upscale voting bloc reliably votes according to the endorsement of the New York Times, a newspaper whose editorial staff are widely seen as reflecting the political and social perspectives of this tribe of voters, so much so that in local New York politics, these voters are known as “New York Times voters”. In Manhattan where these voters dominate, district-level elections are often won or lost according to which candidate receives the coveted endorsement of the Times. These voters are the ones least receptive to populism and most directly interested in good governance.

The natural candidate of the New York Times voters was originally Scott Stringer, the City Comptroller, former Manhattan Borough President, and former state legislator who had always relied on them politically, and who distinguished himself from the field of candidates by having some of the most detailed and thoroughly researched policy proposals, as well as for being the candidate with prior citywide political and governmental experience. Stringer’s candidacy however was derailed by a sexual harassment scandal. Instead, the New York Times endorsed — and its voters reliably supported — Kathryn Garcia, a career municipal employee who rose to commissioner of the Sanitation department, and ran for mayor as a first-time political candidate largely avoiding any polarizing political issues and stressing her technocratic credentials.

The second sub-tribe is the young, very highly educated, very culturally progressive, mostly but not entirely white crowd who mainly live along the east bank of the East River, on the Brooklyn and Queens side directly opposite Manhattan, in the neighborhoods of transition between the Manhattan core and the “outer boroughs”. These voters are stereotypically the young-adult children of the “New York Times voters”, but are defined politically by strong anti-establishment and left-wing politics. They are the political base of the Democratic Socialists of America, a social democratic group that organizes within the Democratic Party to get its candidates nominated in the Democratic Party primaries, and which has been successful in New York most famously with Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the US House of Representatives. They are the strongest supporters of social protest movements and of defunding the police, and can be called “DSA voters” as shorthand.

“New York Times voters” and “DSA voters” share a common culturally progressive identity, and a common suspicion of “machine politics” and of candidates perceived to be too aligned with particular commercial interests, which in this election meant a common repulsion towards Yang and Adams. These two sub-tribes have aligned with each other in previous elections, and Scott Stringer tried to win over the “DSA voters” as well. Stringer spent years preparing for this election by publicly supporting DSA candidates in an attempt to build up goodwill, and was originally supported by the Working Families Party, a social democratic umbrella organization of political activists and labor unions, as well as by many DSA politicians.

When scandals towards the end of the campaign discredited the candidacies of Scott Stringer and of Dianne Morales, a left-wing NGO executive who had also been popular with “DSA voters”, this political tribe quickly coalesced around Maya Wiley, civil rights activist and former lawyer and professor who had previously been chair of the city’s Civilian Complaint Review Board which records complaints of police misconduct and served as a lawyer in mayor Bill de Blasio’s administration. Wiley campaigned on defunding the police, and was not formally endorsed by DSA but received late support of many DSA politicians, most notably Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, and also Massachusetts Senator and former presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren.

The added element of Ranked Choice Voting in this election created the opportunity for candidates to work together and form political coalitions. Indeed in the closing days of the election, when polls showed Adams with a clear lead, Garcia and Yang campaigned together in a joint effort to oppose Adams, and Yang publicly called on his supporters to rank Garcia 2nd, though Garcia notably declined to reciprocate, likely because “NY Times” voters value perceived seriousness and were so repulsed by Yang’s perceived unseriousness as a candidate for mayor that any endorsement of Yang risked alienating them. Wiley for her part declined to explicitly endorse an “anybody but Adams” coalition. But like Yang, Wiley developed a bad relationship with Adams and they often had heated confrontations with each other at the debates. As the most left-wing and most police-skeptical of the major candidates, it was assumed her supporters would rank other candidates below her in an attempt to oppose the pro-police Adams most of all. And specifically because of the commonalities between “DSA voters” and “New York Times voters”, it was expected that most Garcia and Wiley supporters would rank the other one above Adams too. The remaining supporters of Scott Stinger and Dianne Morales were also voters likely to align with this common “liberal-progressive” tribe over the more conservative candidacies of Adams and Yang. Garcia in particular, because she had run a middle-of-the-road, non-ideological campaign, was considered likely to be the 2nd choice of a wide variety of voters who saw her as a compromise candidate.

For all these reasons, when polls closed and election-night reporting showed Adams with a clear lead in the first-round votes, his opponents, and especially Kathryn Garcia, had reason to be optimistic. Though she appeared to be in 3rd place, Garcia also expected to benefit disproportionately from the “absentee” postal votes, which in New York take weeks after election day to fully count, and to be used disproportionately by better educated white voters, a demographic group that Garcia received strong support from in the election-night returns.

In the election-night reporting, Adams led with 31.66% of the first round votes, 137,422 votes more than Garcia. In the full count, including absentee ballots and then the Instant Runoffs, Garcia gained support but ultimately lost the final round to Adams by the very close margin of only 7,197 votes, out of 942,031 cast in total.

Though Eric Adams has only won the Democratic Party nomination, and still faces the general election in November against Republican opponent Curtis Sliwa, the general election is not expected to be competitive, and Adams is presumed to be the city’s next mayor. Having defeated candidates who focused on a variety of policy issues including bicycle and mass transit, education, social services, and economic equality, Adams heads to City Hall with no clear overarching vision for the future of New York City other than to deploy the police force more aggressively to fight crime.