Determining what drives people to terrorism is not an easy task because it is not likely that terrorists volunteer as empirical subjects for scientific studies of their motives for terrorist activities such as jihad and advocacy to spread the culture of martyrdom, and examining their activities from afar can lead to wrong conclusions. Moreover, the terrorist of one group is a freedom fighter of another group, as supporters of suicide bombers will attest.

Researchers admit that given these complexities, however, academic research in this area often concludes that terrorists are originally “normal” people and are not sadistic or psychotic as many believe, but rather are led through group dynamics to do harmful actions to others for reasons they believe are noble. And fair, terrorism here works to reshape that dynamic to show the extremist leadership in a more attractive way to others, it is after numerous psychological experiments that each individual is capable of committing an extremist act under specific circumstances, as Arie W. Kruglanski (1) considers that cognitive mechanisms are the main factor Which underlies radicalism and violent extremism, as it helps in the formation of extremist ideas through the process of reasoning, that is, extracting answers that a person can convince himself with based on previously known information that may be true or false.

It is generally more useful to view terrorism in terms of political and collective dynamics and processes than individual processes, and that general psychological principles—such as our unconscious fear of death and our desire for meaning and personal importance—may help explain some aspects of terrorist acts and our responses to them.

Extremism is a state stemming from a “motivational imbalance” that takes over all other psychological needs, liberating the individual from the rules of behavior accepted in society.

In the case of violent extremism, the question must be asked about the importance of character and emancipatory behavior that uses violence as a means to achieve a particular goal.

Among the cognitive mechanisms adopted are learning from extremists, inferring from previously known information, activating knowledge through close personal contact and weaving communicative relationships within the extremist group. Selective attention, which is focusing on a key idea in an environment of radicalization while ignoring other irrelevant stimuli and inhibiting unwanted thoughts, are among other cognitive mechanisms that contribute to radicalization.

But what are the characteristics that make behavior “extreme”? What are the psychological mechanisms that help in the transition from moderation to extremism and vice versa? We assume that radical behavior can vary and include not only violent extremist ideas but widely different behaviors. For example, violence and disorder can be described as “extreme” behavior, (2) but the same description can be given when following some special diets and some types of sports, attraction to temptations, “deadly” cravings, and cravings for food… Is this considered ‘Extreme’ behaviors are just a way of talking? Or do these behaviors share one psychological core? The answer is yes. These behaviors share a special case of ‘motivational imbalance’, in which a person’s mind is dominated by a need that ‘strongly’ motivates him to satisfy it, at the expense of his other interests.

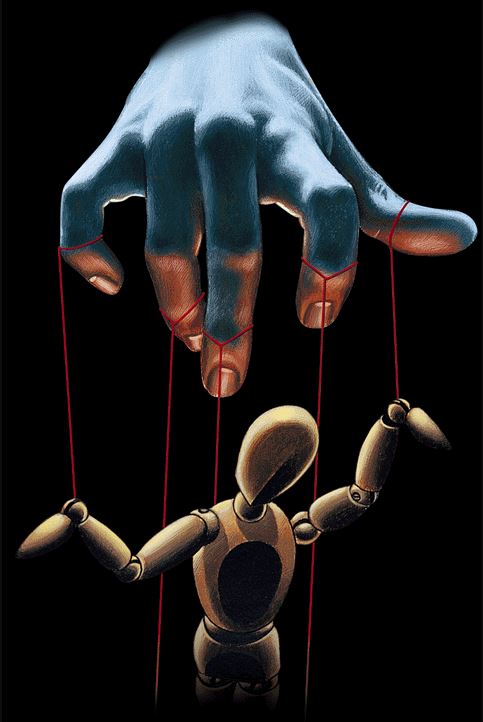

Terrorists are recruited according to precise psychological criteria that depend, for example, on collective disputes that are exploited by leaders to create an internal psychological conflict in the first place that makes the victim involuntarily unite with the extremist leader in order to fight the hostile group, and if we try to define terrorism and terrorists, we will find that Terrorism is an act of “intimidating or terrifying in order to make the target submissive,” because they often could not achieve their goals by means that are consistent with the prevailing social rules in society, and they try to send religious and ideological messages through terrorizing the general public in order to achieve their goals, which often target the state. Among the hypotheses that explain the resort of a group to terrorism is the hypothesis of frustration and relative deprivation, which Ted Robert Jarer talked about in 1970, which is the individual’s awareness of the contradiction between what he obtains (or what his inner group to which he belongs) obtains from rewards and conditions of life and what He expects him, or what he thinks he deserves (or his inner group deserves) and this perception remains constrained within its cognitive limits or produces a feeling of resentment, here produces what is called narcissistic anger, which was touched upon by Gerold Ambost and Richard M. Berlechtian. This hypothesis is concerned with the early psychological development of terrorists, And the formation of their self-centered narcissistic personality and the fulfillment of their personal desires in selfish ways without taking into account the psychology and situation of the other, the terrorist group is not like normal groups such as the work group or friends or others, but it is characterized by special characteristics, like that of ideological groups. One of the most prominent of these features is that it takes the form and structure of nervous relations and the intolerance that accompanies them. The internal structure of the terrorist group is represented in a trilogy: nervousness and the relationship of its members to it, and in the relationship with the guide or the leader of the group, and in the relationship of members among themselves.

At the level of nervous we, there is a likeness of this us that raises it to the rank of purity for impurities, through the sublime and transcendent message over reality, leading to absolute certainty of absolute truth and goodness, where the founder of terrorist groups focuses on the self-image of the member, revolutionary heroism and self-worth, and this is reinforced in ways Crooked where the ego is inflated and made to transcend its peers by giving preference to the terrorist over the rest of his society as he is the chosen one whom God guided to martyrdom for his sake. For the sake of God and the religious cause, as young people who want to commit suicide (martyrdom), but want to get out of humanity to become supernatural beings. The afterlife is rooted in their minds through the sermons of preachers who penetrate their subconscious minds at a moment when the boundaries between the ego and the non-ego, between the real and the unreal, between life and death, are so shaken that it seems right away that the act of self-sacrifice is in the end easy; It becomes an epilogue. At this moment, imagined death so engulfs the self that actual death loses its meaning.

So terrorism never arises out of a vacuum, but rather arises within fragmented groups of the largest social and political opposition movements. This applies to the Babeuf conspiracy during the French Revolution, the Carbonaris in Italy and France in the early 19th century, republican/terrorist groups in France before the 1848 Revolution, the Puritans in the USA, and events culminating in the formation of the Paris municipal government.

The anarchists in Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the USA in the second half of the nineteenth century, the very violent labor movement in the USA, the various groups of anarchists and terrorists in Russia at the end of the last century, the Gallini group in the USA, Free Corps in Germany, White power groups, various leftist groups in the post-World War II Western world, separatist groups in ethnically divided nations, and violent religious extremist groups, including Muslims and Christians. The history of the Western world is utterly replete with movements of political violence. Reviewing this evidence, one realizes that political violence is a two-step process: the first step is to join an opposition political movement, an act that has gradually become legal and legal in much of the Western world since the outbreak of the French Revolution. With regard to the question of the ways that terrorist networks use to attract members to their ranks in the targeted country, the answer is that they do not.

Second, although these political movements often do not adopt violent methods, their ideological foundations may allow some of their followers to justify a turn to violence. And within those movements, especially those that lack internal discipline, there are usually some disaffected who are fed up with the long-running process of reform. These individuals view peaceful means of protest and dissent as futile and adopt stronger forms of dissent. The actions of the state or its subordinate authorities, such as state-affiliated militias attempting to suppress political opposition, often provoke this rejection of peaceful protest methods, espoused by the bulk of opposition groups, into political violence. These actions usually generate a sense of moral anger among young opponents and lead them to believe that violence is the only way to political change.

As Sagman (3) said, most terrorist activities in the West in the past two hundred years are self-generated, organized and financed spontaneously. At the end of the nineteenth century, the leaders of the opposition movements did not accept the terrorist attacks “from the lone wolf” called individual revenge. In fact, the larger movement recognized that the damage done by these terrorist attacks had dispersed rather than mobilized individuals at a massive level, and that the reward for individual attacks had waned over time. This historical framework helps explain some of the apparent puzzles that arise from the focus on this “new” wave of new jihadist terrorism in the West.

- Arie W. Kruglanski (born in 1939) is a social psychologist known for his work on goal systems, regulatory mode, and cognitive closure. He is currently a distinguished professor of psychology at the University of Maryland, College Park.

- Sullwold, Lilo. “Biographical Features of Terrorists.” In World Congress of Psychiatry, Psychiatry: The State of the Art, 6. New York: Plenum, 1985.

- Stohl, Michael, ed. The Politics of Terrorism. 3d ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1988.