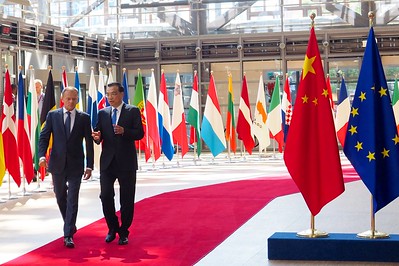

The European Union is, as so often, attempting a difficult balancing act, oscillating between economic interests and a value-based foreign policy. Shortly after the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) was announced to be concluded in principle, it already seems to be falling apart before it even comes into effect. After EU sanctions on China due to human rights abuses by the Chinese regime led to counter-sanctions against European MEPs, the EU Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis has admitted in an interview that ratification of the agreement is not feasible given the circumstances. At the same time, the pandemic has only increased the dependence of the European economy, and especially Germany’s, on China and its desire for European products.

Betting on China is, however, economically and geopolitically shortsighted. China’s increasingly aggressive behaviour on the diplomatic stage, combined with its horrendous human rights abuses in Xinjiang and elsewhere, need to be addressed self-assuredly by liberal democratic states. The case of Australia should be a cautionary tale of how economic dependence on an autocratic state can have severe consequences when geopolitical and diplomatic tensions arise. China accounted for 39% of Australian exports and 27% of imports in 2019-20, making it the country’s number 1 trading partner by far. But after Chinese aggression and political meddling in Australia led to a change in Australian foreign policy, China imposed tariffs on Australian products such as wine, which severely hurt the Australian economy. Some analysts predict that an all-out trade war could cost as much as 6% of Australia’s GDP. In Europe, self-censorship out of fear to anger the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is one of the first worrying signs of how economic dependence may lead to a betrayal of liberal values. In 2018, a high ranking German official censored an intelligence report about Chinese influence in order not to threaten the significant economic ties with China.

The once-held belief that trade liberalization with China would lead to a slow political liberalization in China proved to be wrong. The prospect of growing economic openness and wealth leading to a more open society may have seemed possible, but internal political developments in the CCP – especially since Xi Jinping’s power grab – led to a different outcome. China has significantly profited from its access to global markets since the 1980s, but the country turned more and more totalitarian in the last years.

The question now is what kind of policy Europe should pursue towards China instead. The first necessary step is an honest self-assessment. Europe is on the economic decline; it has been for years, and the trend will continue. In the 1960s, the EU28 member states (including the UK) have accounted for one-third of worldwide GDP; this number has shrunk to 15 % today and will continue to decrease to 10% by 2100. This in itself is not necessarily an entirely negative trend, but it puts Europe’s place and power in perspective. China, meanwhile, is expected to become the biggest economy by 2030 – overtaking the US – and having a 17.4% GDP share of the world economy in 2100. Thus, in the long-term, the EU will play a much smaller role in the world economy – while China’s rise seems to be inevitable.

Expanding economic power will also translate into more geopolitical power for China. And given China’s track record, the country will be no force for good in world politics. Europe, therefore, needs to be a liberal counterweight to it, but given its economic decline, it needs to choose sides. The EU, its member states but also the UK, are simply too small and economically insignificant to counteract Chinese dominance. Therefore, Europe needs to align with the most competitive liberal democratic adversary of China – the US. Despite all its woes, the US remains the most dominant geopolitical and economic force in the world. In Europe, there still seems to be a lot of sympathy for enjoying the economic benefits of partnering with China while ignoring the geopolitical consequences. If Europe, however, wants to avoid being in an Australia-like situation, it should align its Chinese foreign policy with the US and its democratic partners in Asia. The timing for taking such a decisive standpoint has never been better. After Obama’s pivot to Asia and Trump’s chaotic presidency, a renewed transatlantic partnership seems to be possible with the Biden administration.

Joe Biden has taken a clear stance on China and announced that the country can expect “extreme competition” from the US. Europe should not be naïve and believe that it can take a middle position in this standoff – it has to choose sides. And given the latest developments, it appears that the mood in Europe is shifting towards a more assertive policy against China. The failure of the EU-China investment agreement is just one example. The EU moreover plans to introduce restrictions for Chinese investments in core European technologies. Italy has shifted from the pro-China camp to a more critical approach under its new prime minister Mario Draghi by blocking Chinese acquisitions of Italian companies.

But more is to be done. Economic dependence on China needs to be limited if not reversed. A new transatlantic trade agreement would be a good first step to dampen any economic downsides of increasing trade conflicts with China. The announcement made this weekend by Commission President Ursula von der Leyen that the EU will restart talks with India for a trade deal is another promising step. Furthermore, the EU and the US should work intensively on countering China’s influence in developing nations – offering countries alternatives to Chinese investments, such as the Belt and Road Initiative. The EU’s decline to help the tiny Eastern European nation of Montenegro with its struggles to repay a €1 billion loan to China was a mistake. It would have been a powerful sign in countering Chinese loan diplomacy.

The European Union would be well advised to use the current momentum to pursue a strong transatlantic alliance with the United States. A more value-based and outspoken policy against China may have short term economic drawbacks, but in the long term, too much dependence on the Chinese market would threaten Europe’s ability to criticize the Chinese Communist Party freely.