In previous articles, we frequently talked about opportunities for economic development and what kind of policy measures have to be provided in order to facilitate sustainable and inclusive global economic growth. But regardless of which region in the world we are looking at – and this becomes especially obvious amidst the corona crisis – one thing is crucial and decisive for a prosperous society: infrastructure. Still, the financing and funding of infrastructure presents challenges that need to be met, both financially and politically. Thus, in this article, I’d like to outline some approaches of how to close the infrastructure financing gap in order to open the door for global prosperity and economic upswing.

When talking about the lack of capital in the infrastructure market, we first have to take a look at how these projects are financed. Historically, investing in infrastructure has been solely a public responsibility. However, the privatization of infrastructure investments was the consequence of an underperforming public sector in the 1990s – especially in low income countries. Even three decades later, however, economic and policy advisors are still at loggerheads with each other about the role of the private sector in infrastructure finance. As infrastructure projects are characterized by high up-front costs, a lack of transparency, capital intensity and complex legal structures, the number of market players that are able to provide capital is naturally limited.

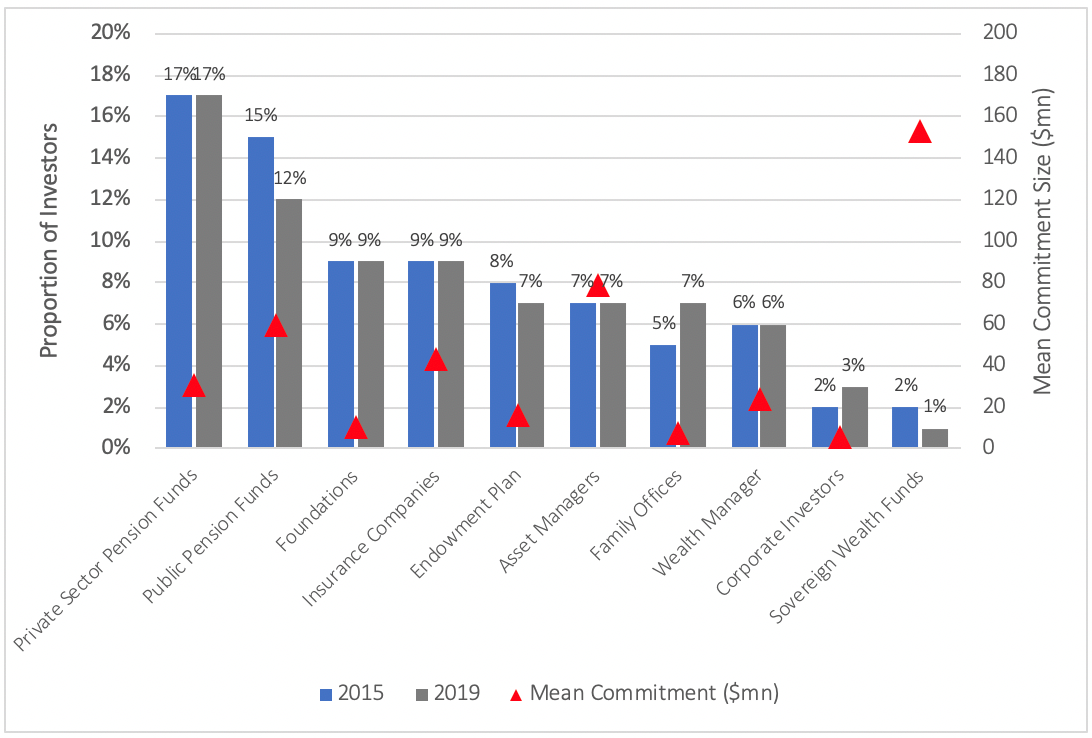

This can be highlighted by the share of total investments each type of investor in the private market is accountable for (cf. Figure 1). Also, as indicated by the red triangles, the mean commitment in infrastructure capital of each investor type plays an important role when speaking about barriers for entering the infrastructure market. Private Pension Funds, for example, have a large market share of around 17% but are at the same time only able to commit an average of around $30mn to each project. This is determined by their regular need for liquidity, legal diversification quotas (e.g. the Solvency II Directive for European insurances) and required risk-return-profiles.

Although sovereign wealth funds were accountable for only 1% of the whole volume in 2019, their mean commitment size is by far the highest – both in relative and in absolute figures. This can, inter alia, be explained by their limited need for liquidity and long-term investment horizons. For asset managers, the amount of deployable capital – so-called dry powder – is also a decisive factor for infrastructure development in certain regions. Last year in Europe, for example, Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) were on an all-time low, while fundraising activities were on an all-time-high. This contrary movement of funding and deal activity in a compressed investment market led to more extensions of existing investments and the refuge of some asset managers into niche strategies. As a consequence, the development of new infrastructure projects was thwarted.

To get the big picture of the global infrastructure market, we also have to consider the global demand for infrastructure in general. Oxford Economics and the Global Infrastructure Hub, a G20 initiative, estimate an annual investment need of $3.7tn between 2016 and 2040 – an increase of 19% in comparison to current trends. This demand is also driven by the deterioration of existing infrastructure, shifting demographics and urbanization trends. From a global perspective, it is important to mention that a lack of infrastructure capital is not only to be found in developing countries but also in well developed countries e.g. from the European Union (EU). Within the aftermath of previous European crises for example, governments put a strict cap on public spending that ultimately led to a shortage of infrastructure investments and stresses the need for private capital.

Within the debate of the privatization of crucial state infrastructure, Public-Private-Partnerships (PPPs) then emerged as a popular financing instrument. The underlying idea of PPPs is a cooperation between the public and private sector with a distribution of risk to those parties that are the most capable of holding them. But market asymmetries and the vast need for extensive expertise limit overall capital supply.

In contrast to public markets in general, this lack of information especially occurs during the development and construction phase. These data gaps might be closed with taxonomies that allow standardized analysis and thus more transparent indicators (e.g. in the form of adequate benchmarks) for decision-making. Also, the efficiency of Private-Public-Partnerships could be enhanced by multilateral development banks (MDBs) by bundling expertise, public and private capital and due diligence resources and by providing cheaper co-investments. Creating standardized investment opportunities around MDBs might also enable securitization of infrastructure investments and hence a widening to more potential infrastructure investors. For institutional investors to invest in infrastructure, matching risk-return-profiles and investments that correspond to return expectations and liability structures are mandatory. Also – though certainly rather a topic for broader discussion – corruption in developing countries needs to be faced to ensure a more efficient use and deployment of capital. As countries might not be able to implement holistic approaches on the national level in the short-term, initially removing barriers for local governments could increase the number of investment opportunities substantially. In general, policy packages are advised to be kept simple in order to not over-regulate the asset class and avoid opposing effects.

As mentioned before, the demand for infrastructure capital remains unabatedly high. Current trends and obstacles show that it needs both political and economic effort to tackle challenges with regards to infrastructure as an asset class. Previous issues with insufficient risk-return-profiles, inefficient PPPs or corruption in developing countries need to be tackled to close the infrastructure financing gap. However, large amounts of liquidity in private market vehicles give reason to hope that – on the premise of targeted policy measures – infrastructure needs could be met in the future and therefore lead to overall prosperity and growth in the respective regions or countries.