This article is the part of a series by the IFLRY Climate Change Programme, looking at how different countries are implementing the Paris Agreement. An introduction to the series can be found here.

The Mediterranean is one of the regions of the world most threatened by the impact of global warming. Projections forecast an increase in average surface temperatures of 2.2 to 5.1 °C, but the greatest menace to the Mediterranean Basin is the acceleration of the desertification trends already prevalent in the region, with thriving cities such as Lisbon and Seville potentially finding themselves in the middle of the desert by the end of the century. Knock-on impacts on water management, agriculture, biodiversity and even migratory movements make climate change an existential issue for the Mediterranean.

It is perhaps for this reason that public opinion in Catalonia is acutely aware of the need to take action. 90% of Catalans say that they are “rather concerned” or “very concerned” about climate change, with 81% reporting that they take action on a personal level to minimise their carbon footprint.

Catalonia

is at the forefront of the fight against climate change. Carbon dioxide

equivalent (CO2e) emissions for 2016, the most recent year for which

complete data are available, were

44.53 million tonnes. This represents 13% of all the emissions of Spain

and 1% of all the emissions of the EU28, which at 5.98 tonnes of CO2e

per capita is significantly lower than the demographic weight of Catalonia in

these geopolitical entities. However, 2016 emissions actually increased

slightly compared to 2015, continuing a three-year rising trend after many years

of decreases, and there remains much work to be done.

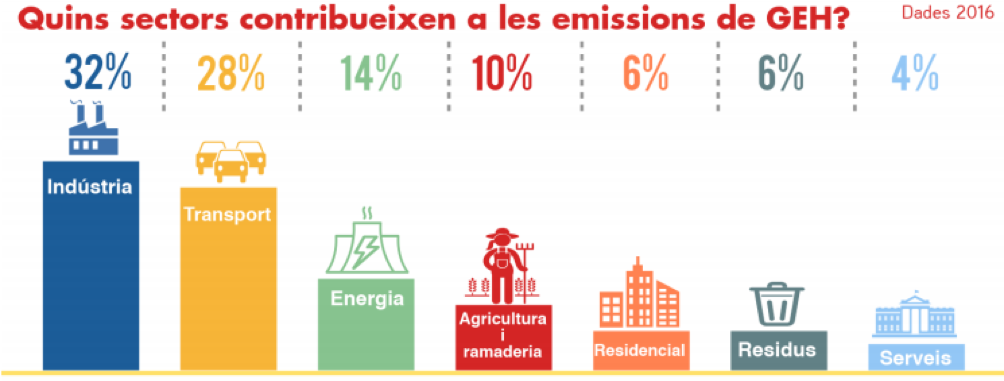

Who emits what

Greenhouse gas emissions in Catalonia are broken down as follows: 32% for industry, 28% for transportation, 14% for energy, 10% for agriculture and husbandry, 6% for housing (including heating), 6% for waste disposal and 4% for services (source)

Industry is the single biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in Catalonia. Mining, metallurgy and chemical industry emit the greatest amounts of these gases, together with companies in other sectors that produce and use halocarbons and sulphur hexafluoride in their industrial processes. The major contribution of industry to greenhouse gas emissions in our country has made it an obvious target for legislators. The Law on Climate Change approved by the Parliament of Catalonia in 2017, which we will discuss in greater detail later, includes new taxes on industrial sectors that emit greenhouse gases, starting at an average of €10/tonne of CO2 in 2019 and gradually rising to about €30/tonne in 2025.

In addition to the usual issues with CO2 emissions from road and air transportation, the importance of sea transportation adds an extra dimension to the state of play in Catalonia. The rise of the Port of Barcelona and other Catalan ports as hubs for trade with Asia and cruise destinations presents economic opportunities, but also environmental concerns. In Barcelona, the leading cruise port in the world outside Florida, gigantic ships emit large amounts of nitrous oxide (N2O), a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than CO2. Here again, the Law on Climate Change will roll out new measures to disincentivise these emissions, levying €1,000 for each tonne of N2O released by these ships while docked.

The energy mix used for electricity generation in Catalonia is comparable to that of other developed countries. Generation facilities with a capacity of 50 MW or more include three nuclear plants, nine combined-cycle power plants, ten hydroelectric power plants and two combined heat and power plants.

Spain “taxes the sun”

The fight against climate change in the energy sector has been severely hamstrung by legal uncertainty. Starting in December 2010, the Spanish government smashed up the existing legal framework and retroactively cut subsidies to photovoltaics and other low-carbon power sources. Retroactivity and legal uncertainty tend to be bad things in general, but they are even more destructive to investors in cutting-edge fields such as renewables. A report estimated that these measures have pushed over 92% of photovoltaic plants and 55% of wind farms in Spain into bankruptcy or debt restructuring, while even those that survive will still suffer a loss of revenue throughout their life cycles totalling billions of euros across the country.

Although the socialist government in power between 2004 and 2011 promoted the adoption of measures to improve energy efficiency in housing, subsequent legislation in the aftermath of the financial crisis also hampered the fight against climate change in housing. In addition to banning solar panels in shared buildings, thereby excluding the vast majority of Spaniards who live in flats, it turned the process of installing solar panels into a bureaucratic nightmare, required the payment of substantial fees to utility companies and stipulated fines of up to €60 million (!) for failure to obtain the proper permit. Even though no fines of this magnitude were ever issued, this and the other provisions of the law had an obvious chilling effect. Fortunately, the new government led by Social Democrat Pedro Sánchez has repealed this legislation, but its impact, at a time when housing energy efficiency should have been taking off, was dire.

Fighting climate change the decentralised way

As a territory located in the European Union (EU), Catalonia is covered by the INDCs submitted by the Union. Through these INDCs, the EU and its Member States are committed to a binding target of an at least 40% domestic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 (base year). The objective for 2030 doubles the 2020 target, which is a 20% emission reduction compared to 1990 (including the use of offsets). EU INDCs also aim to further decouple GDP from greenhouse gas emissions. Catalonia also serves in its own right as a co-chair of The Climate Group’s States and Regions Alliance.

The Government of Catalonia’s main tool for attaining EU targets and its own climate change commitments is the aforementioned Law on Climate Change, approved on 27 July 2017 by a very large majority of the Parliament of Catalonia. It is described as one of the most ambitious and ground-breaking pieces of climate change legislation in the world. Its main points are the following:

- curbing greenhouse gas emissions and transitioning towards a low-carbon economy

- consolidating and enhancing previous initiatives in this field

- coordinating public authorities, organisations and societies to fight climate change

- making Catalonia a leader in researching and using relevant new technologies

- reducing the country’s dependence on external energy resources, particularly fossil fuels

- engaging other countries through involvement in joint projects and international fora

- establishing a public Climate Fund to implement mitigation and adaptation measures

- levying taxes on activities that emit large amounts of greenhouse gases

The law puts Catalonia on the path towards a sustainable economy by enshrining a commitment to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 40% by 2030, 65% by 2040 and 100% by 2050. In other words, it aims to make Catalonia a zero-net carbon country by the middle of the century. It also has a social component, guaranteeing access to basic energy and water resources for every citizen.

Environmental hazards

As with the development of renewable power and the promotion of energy efficiency in housing, the Catalan Law on Climate Change was hampered by ill-advised political choices made by the Spanish government. In a context in which Madrid was systematically challenging before the Spanish Constitutional Court a wide range of laws approved by the Parliament of Catalonia to flex its muscles in the run-up to the Catalan independence referendum of 1 October, the Law on Climate Change was one of the victims of this posturing. The move, which was described as “insane” by international experts including the head of the leading climate change think tank IDDRI, caused the Law on Climate Change to be suspended. Almost a year and a half later, the Constitutional Court has finally lifted the suspension of the majority of provisions in the law, but again political brinkmanship in Madrid has caused serious damage to the fight against climate change in Spain and in Catalonia.

Aware of the importance of keeping the temperature increase as low as possible, both Catalan media and the society of our country are strongly committed to combating climate change. Unlike the fight against other forms of pollution (e.g. limitations on diesel vehicles and old cars in town centres), the measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions have met with very little opposition. Where it exists, it relates mainly to concerns on the impact of these measures on electricity bills. Although the effect of the Law on Climate Change on energy prices is fairly negligible, this is a sensitive topic because Spain has some of the highest electricity costs in Europe, there have been a series of significant price hikes over the last couple of years, and voters understandably view the cosy links between the government and utility companies with suspicion. The social aspects of the Law on Climate Change will help to allay these concerns.

Catalonia has something that is unfortunately very rare in the global fight against climate change: unity of purpose. The vast majority of society, together with public authorities, private business and media are concerted in their determination to bring down greenhouse gas emissions. The widespread climate change denial that plagues other countries is non-existent here. It is too great an opportunity to let it go to waste with ill-advised political decisions. Let the Catalan Law on Climate Change be a template for Europe and the world to put regional policy at the heart of the fight for our planet.

Alistair Spearing is the European Officer of the Catalan Nationalist Youth (JNC) and a member of the International Board of the Catalan Democrats (PDeCAT). He has been a scientific translator specialising in life sciences for almost a decade now. He is active on Twitter as @Alistair_SBD

1 comment